While looking for summer internships, a question I frequently paused at was “How many languages do you speak?” For most people, that isn’t a point of contention. But for me, it was a reminder of what I lacked.

I was born in Chicago and lived in the greater area my entire life. Ethnically, I am half-Mexican and half-Indian. My mother is a first generation Mexican-American and my father immigrated from Kerala, India when he was just 10 years old.

When I was a baby, my mother’s aunt would watch me while my parents were at work. She only spoke Spanish, so some of my first words were also in Spanish. But at home, my parents only spoke English.

Eventually, I didn’t need babysitting anymore, and I started going to school where we also only communicated in English. This meant that I did not learn to speak Spanish with the people I love.

This felt isolating.

I have been called a “no sabo” kid before in a joking way – sometimes, I even refer to myself as a “no sabo,” as well. The phrase doesn’t hurt my feelings, but acknowledging my insecurity is difficult regardless.

The phrase “no sabo” is an incorrect conjugation of “no sé” in Spanish, meaning “I don’t know.” It also refers to young Latine Americans who are not fluent in Spanish.

The term has gained popularity in recent years after Latine Americans began using the phrase to reclaim pride in their identities.

Sophie Lesanek, a 23-year-old content creator and social media manager from North Carolina, started making videos on Instagram last December about her experience.

Lesanek’s online platform reflects her mixed Czech and Mexican heritage and how she has learned Spanish over the last few years. By posting more about being a “no sabo,” she hopes to “fill a gap” in the topic.

“Society makes it to be like, ‘If you’re Mexican, you must speak Spanish.’ And I didn’t,” she said.

Lesanek said that she has “always felt a kind of identity crisis” from being of three different cultures since she was born in the United States.

Akin to Lesanek, having a multiethnic background, I never quite knew where I fit in either. My mother has told me that others shouldn’t expect me to speak Spanish because my household is not fully Mexican-American.

And yet, I still put an inexplicable amount of pressure on myself to know the language.

Now in college, when most assume that I do speak Spanish and I re-explain that I don’t, a wave of shame washes over me.

Lourdes Torres, the chair of the Latin American and Latino Studies Department at DePaul, said that Latine parents have different reasons for not passing Spanish down to their kids, but one of the biggest ones comes from the fear of being ridiculed.

“They have suffered a lot of humiliation and discrimination because of their lack of knowledge of English, and they don’t want their kids to experience the same thing,” Torres said.

Another reason why parents may not teach their kids Spanish is because of the myth that being bilingual causes confusion or hinders the learning process for another language, she added.

“The parents are trying to do the best for their kid. They just have bad information about what that means,” Torres said.

Unfortunately, the loss of the Spanish language can be “devastating.”

“Kids who, for example, stop speaking Spanish, and then they go home to Mexico and their relatives are making fun of them, or they can’t speak to grandma. That’s a huge loss,” Torres said.

The disconnect that stems from not speaking Spanish may lead “no sabo” people to feel that they are not Latine enough.

“You feel bad… You [feel like you] failed this test of relationship with your culture,” Torres said.

But Lesanek and Torres believe that speaking Spanish should not dictate a person’s connection to their Latinidad.

“The true meaning of what a Latina is does not come from language,” said Lesanek. “It comes from within.”

Torres said she is “glad that this [‘no sabo’] movement exists,” and people are more inclusive of diverse expressions of Latine culture.

“I feel like it’s really mean for people who have access to Spanish to tell other people ‘you don’t belong to our community,’” Torres said.

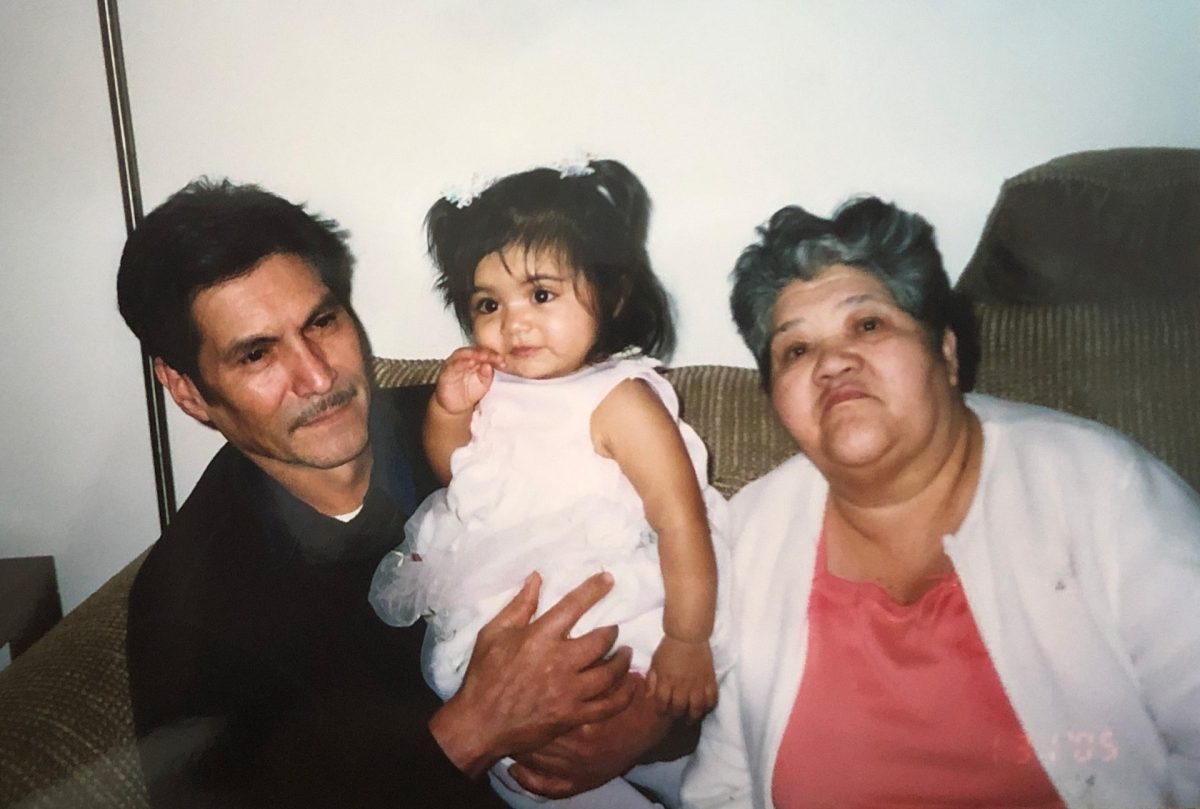

My mother’s parents only spoke Spanish. Although I spent much of my time with them as a kid, I never had full conversations with them. When they would speak to me, I was only able to piece together parts of their sentences from what I knew.

That still breaks my heart. It felt as if there was a glass between us; I could see them, but I couldn’t understand them.

What ultimately transcended language were the smaller acts of love I carry with me to this day.

My grandmother would buy me princess dresses to twirl around in, and she would let me play with her hair. My grandfather would pick me up from school in his van and let me sit in the front seat, probably against my mother’s better wishes.

My lack of Spanish never made me less of a granddaughter to them. So why should I let it make me feel like less of a Latina to myself?