Worldwide demonstrations express solidarity, concern about climate change

Amid another year of frustration about continuing climate change, throngs of environmental activists congregated throughout the world on Sept. 21 to gather in a series of marches and environmentalist demonstrations referred to as the People’s Climate March.

More than 2,700 events took place globally. According to the Associated Press, more than 580,000 people demonstrated in these global events, making it the largest environmental gathering in history. CBS reported that more than 300,000 people took part in New York City’s march alone.

Although global demonstrations mainly occurred on the 21st, environmentalists in New York City followed the People’s Climate March with another subsequent protest, dubbed Flood Wall Street, the next day.

The global demonstrations were meant to express public solidarity about environmental concerns in advance of a United Nations Climate Summit, which occurred in New York City on Sept. 23. New York City’s demonstrations in particular targeted corporations that were deemed responsible for continued carbon emissions, as they marched through the heart of Manhattan outside many of these companies’ offices in Midtown and Wall Street.

“It does seem that people are indeed understanding more of the impact of their own country’s emissions and externalities on the rest of the world,” Kelly Tzoumis, a DePaul environmental policy professor, said.

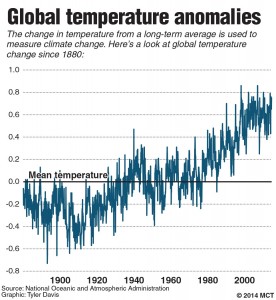

Concern regarding climate change has become a hot topic over the past few years for policymakers and critics alike. The National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) reported that the average global ocean temperature had hit a record high this August, and a U.N. report obtained by the Associated Press on Aug. 26 warned that climate change may already be irreversible to a certain degree.

“Does (temperature) necessarily go up every year? No,” Mark Potosnak, a DePaul assistant professor in environmental science and studies, said. “But on any scale, the Earth has definitely warmed up over the past 150 years.”

In addition to the melting of the polar ice caps and the rise of global sea levels, many climatologists blame greenhouse gas emissions and climate change as the culprit for many weather-related phenomena, including the polar vortexes that hit Chicago and the Midwest last winter.

“We cannot say that each extreme weather event is directly caused by global warming,” Potosnak said. “However extreme events, such as droughts in California or the extreme rainfall and flooding we had this summer, are definitely happening at a higher frequency. Paradoxically, warming may have even been a factor in the polar vortexes (that hit Chicago this winter).”

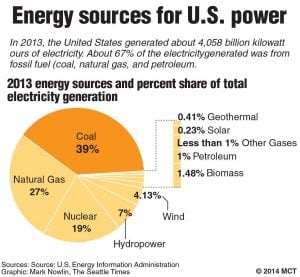

According to the Global Carbon Project, 2013 marked a record total of 36 billion tons of human carbon emissions globally — a 2.3 percent increase from the previous year and a 61 percent increase from 1990. The United States was the world’s largest per-capita emitter of carbon in 2013. However, developing nations such as China and India have been quickly rising in emissions, and China now emits more carbon per-capita than the European Union and more total carbon than any other nation.

“Historically speaking, development has been difficult to achieve without polluting utilization of natural resources, from wood to oil,” Tzoumis said.

Amid these concerns about rising greenhouse gas emissions, many wonder what type of policy changes, if any, will follow.

“As far as U.S. environmental policy goes, Obama will continue to stretch executive order and regulations as much as possible,” Tzoumis said. “However, this command-and-control approach isn’t enough. For policy to work, government needs to fully legislate and work with industry, and do better in economically incentivizing industries to reduce their own emissions. However, that (type of) legislation requires Congress to work across the isle to pass laws, which isn’t happening.”

Internationally, the U.N. is hoping to draft a global, legally binding agreement addressing climate change. No formal global policies were drafted at the Sept. 23 U.N. panel, as it functioned mainly as a discussion among world leaders. However, the U.N. intends to enact tangible policies at the Paris Climate Conference, which will occur in early 2015.

“The problem is that at the international level, there’s no real regulatory body,” Tzoumis said. “The U.N. is more of an advice body, and nations don’t necessarily have to follow or ratify their say. There’s no equivalent to, say, the Environmental Protection Agency.”

Despite the massive environmentalist gatherings that occurred at the People’s Climate March, there are still questions over whether mainstream public opinion is enough to pressure national governments into following U.N. policies or enacting more of their own regulations.

“(Environmentalist pressure) really occurs when people can visually see things,” Tzoumis said. “In the ‘80s when people could see NASA’s

pictures of the ozone hole, the international community reacted and the hole has now been recovering. Unfortunately, climate change has been so incremental that people have been slow to visually seeing things.”

Although the size of the demonstrations shows that overall public opinion may be growing in its concern over greenhouse gas, the question remains as to whether human reaction to climate change may be too late.

“(Climate change) is almost like a car,” Potosnak said. “It’s moving and there’s no easy way to hit the brakes. Many think the Earth may not go back to normal; once the ice caps melt, they won’t necessarily come back. As humans, we have to realize it’s getting worse. Action can start.”