Take Back the Night extends support to sexual violence survivors, highlights institutional shortcomings

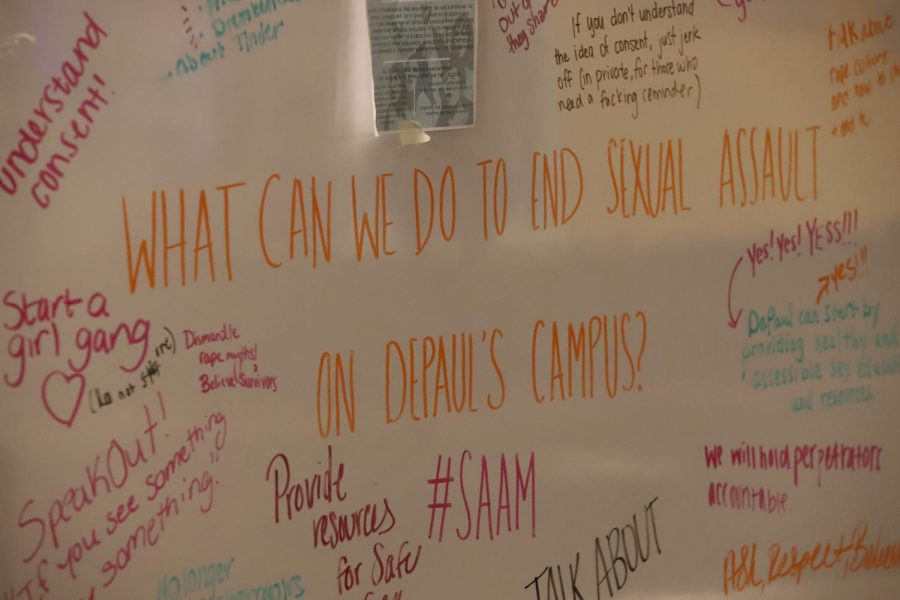

Students write suggestions for how to curb sexual assault on campus on a white board at the Take Back the Night event.

Technicolored shirts displaying personal narratives and messages of support for survivors of sexual assault covered the Schmitt Academic Center as a part of the Clothesline Project, just one component of DePaul’s Take Back the Night.

Charlotte Byrd, one of the event’s organizers and member of Students for Reproductive Justice (SRJ), says that the addition of the Clothesline Project added a fresh component to the annual event.

“We were really into doing something art-based, expressive and taking up space,” Byrd said. “We really liked how it was up to the person making the shirt and what would go on it.”

Expression was key as survivors shared their experiences throughout the evening. Students from multiple student organizations stood in solidarity with survivors and chose to speak in front of the crowd, each offering a different perspective.

Nina Wilson, a student worker at the Women’s Center, read a poem to the audience that she wrote about dealing with trauma and self-assurance, evoking tears from nearly all attendees. In contrast, SRJ members Brenna McBride and Lucy Kelliher used their time to highlight DePaul’s “institutional failing” to provide a safe space for victims, garnering snaps and hollers from all corners of the ‘pit.’ Other students from groups like Women’s March DePaul, Students for Sensible Drug Policy and Students for Justice in Palestine pledged their groups’ numbers and support for all future events related to women’s rights and sexual violence on campus.

The event concluded with healing circles behind closed doors. Sexual and Relationship Violence Prevention Specialist Hannah Retzkin said that these circles, which were suggested by Ann Russo, director of the Women’s Center, provide a unique aspect not found at other events.

“At other universities, like where I went to college, there would be an open speak out where people would come up and speak, but then go sit down,” Retzkin said. “There wasn’t that welcoming sense of community of coming together to provide healing.”

Take Back the Night, a foundation which aims to end all forms of sexual violence, began as independent protests across campuses in the 1970s. From San Francisco-based protests surrounding pornographic “snuff” films in 1973 to the 1975 murder of microbiologist Susan Alexander Speeth in Philadelphia, these efforts were directed at protesting violence against women.

It was not until 2001, however, that the foundation became official. The first woman in the United States to publicly come forward as a victim of campus date rape, Katie Koestner, reached out to early event organizers in hopes of integrating efforts to spread awareness more effectively, according to the organization’s website.

While its mission initially focused on violence against women, it has spread to be inclusive of all survivors and systems of oppression as it has become more pervasive globally.

Retzkin says that the event is especially important given typical perspectives of sexual violence.

“We tend to focus on the individuals,” she said. “That’s important but that’s not it … Even if we think that sexual violence doesn’t affect us, it does. It affects every single person in our community.”

Although the event focused on providing support for survivors, it drew attention to institutional failure to adequately deal with sexual violence on campus.

“They think that [these policies are] doing things, or are enough, but it’s not,” Byrd said. “Inherently — those policies, offices and whatever else is set up to appear as though they will provide care — are flawed. Even access to the care offered by the university is very limited in who can do that and who has that ability.”

Myranda Bahr, another member of SRJ, says that these feelings results from an unwillingness to offer basic resources — such as condoms — to its students.

“They don’t like to acknowledge that sex happens among their student body,” she said. “Or that sexual assault happens among their student body.”

Multiple organizers expressed their frustration with DePaul in its selectivity in issues in which they voice support.

“I think DePaul chooses who to support and therefore it’s not actively saying that ‘We don’t support certain people,’” she said. “It’s just who’s the most supported, who gets the most money—and then a lot of people fall short.”

“[DePaul] is very selective in terms of what awareness is being brought to,” Byrd said. “The more they can push something down and make it not exist — something that will make them look bad or that they’re not doing their jobs — they will do.”

Organizers of the event did not let the lack of support from the administration deter them from creating the safest space possible for survivors.

“I personally want people to feel like they’re seen,” Wilson said. “I really fluctuate with how much I use the word survivor because not everyone feels like a survivor. Your feelings change all the time about that, so people who have unfortunately experienced sexual assault I want them to feel seen and welcome in one space at least.”

Belinda G. Smith • Apr 23, 2019 at 12:40 pm

You used my niece’s photo withour her permission. You hijacked her experience for your own mediocre gains. “My trauma does not exist so that you may write about it.” So much for helping women. Shame on all of you.