DePaul expects $14m tuition revenue shortfall

Credit: Courtesy of DePaul University

President Esteban at a town hall.

Since the 2019-2020 school year began, President A. Gabriel Esteban’s administration has been clear about the university’s top priority: Improve enrollment. But that won’t be so simple in the face of a $14 million tuition revenue shortfall.

This past week, Esteban hosted a Leadership Town Hall for faculty and staff alongside Interim Provost Salma Ghanem and Executive Vice President and CFO Jeff Bethke to break down DePaul’s financial struggles, expectations for next month’s budget proposal and how to execute Esteban’s vision for the future.

Esteban recapped his series of ambitious goals. If all goes smoothly, he hopes DePaul will rank among the top 50 urban universities in the United States, as a top-10 Pell-aided university and a top-5 private catholic university by 2030. He said the university is also aiming to bring its endowment to $1 billion by 2030.

Between fiscal year 2018 and 2019, DePaul’s endowment grew by 17 percent (roughly $100 million addition) to just shy of $700 million.

“We set high goals for our students and we expect them to achieve that,” Esteban said to a room of more than 500 faculty and staff. “Why shouldn’t we expect that for ourselves?”

In order to get there, DePaul will need to address its waining enrollment figures to contend with an eight-figure shortage in tuition revenue for the 2020 fiscal year. Esteban said they do not expect cuts for the current fiscal year, and even anticipate an operating surplus thanks to an eight-figure donation and a “commitment to control costs.”

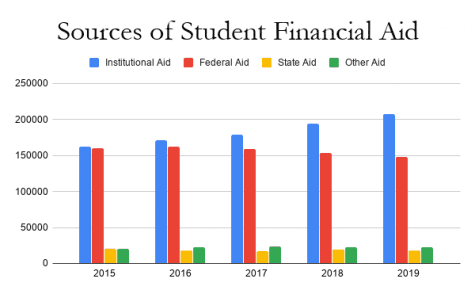

Data from IRMA.

Despite welcoming the largest freshman class on record (beating projections by 5 percent), DePaul missed its enrollment projections by a margin that Esteban described as “fairly significant.” Transfer student enrollment fell 10 percent shy of projections, and continuing undergraduates and graduate students both enrolled 3 percent short of projections. That works out to more than 650 fewer students across those three groups.

DePaul reported a 2.1 percent decline in total enrollment in 2019, while national enrollment in higher education fell 1.7 percent. While there are many factors driving enrollment rates down, Esteban said the main reason is a simple matter of demographics.

“There is nothing we can do unless people start giving birth to 18-year-olds,” he said.

There are two headline tactics for improving enrollment: more aggressive out-of-state recruiting and investing in new programs. Esteban said he was surprised to learn that DePaul did not engage in out-of-state recruiting when he arrived on campus in July 2017. Today, DePaul has two recruiters in California, one in Texas and one working across the east coast; California is now the second most common state of origin for DePaul students, and enrollment from Texas has also seen a notable increase.

Ghanem said DePaul’s main competition comes from other schools in Illinois, where DePaul has an advantage in its appealing ratio of resources to students, but is at a competitive disadvantage in terms of price — something she said the university will never be able to compete with.

Private schools like DePaul do, however, tend to offer more financial aid than public universities. In an effort to coax public university students to go private, DePaul has continued to increase the amount of financial aid they offer each year. Since 2015, institutional aid has steadily increased, growing from $162,000 in 2015 to more than $207,000 in 2019.

Investing in new programs will be the more challenging task due to shrinking margins in the budget, Esteban said. So the key will be freeing up cash wherever it can be found.

The university will look to make around $11 million in expense cuts, which Esteban said will fall disproportionately on the administration. One big-ticket item on the chopping block is DePaul’s executive offices in 55 E. Jackson Blvd., where the school currently leases 160,000 square feet of space. That lease will end in December 2022, but in order to move into the DePaul Center just down the block, they will need to use space currently occupied by the City of Chicago. Because the city’s lease won’t end until the end of 2023, Bethke is working with owners of both buildings to determine a precise moving date, according to a university spokesperson. They hope to iron out the precise timing in the coming months.

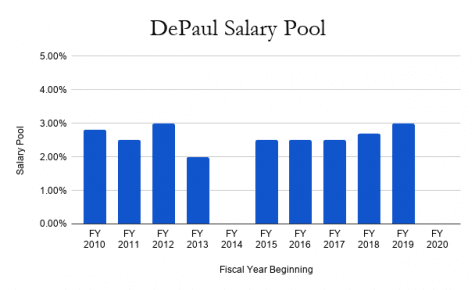

The proposed budget for fiscal year 2021 — which will be reviewed by the Board of Trustees in March — isn’t expected to make faculty happy. Bethke said that while the university usually makes a point of raising salaries each year, the new budget won’t include pay increases for full-time faculty and staff. DePaul’s salary pool takes a percentage of all salaries (usually around 2 percent) and redistributes that figure in the form of raises.

Bethke called the decision to freeze salaries “unfortunate” and a “one-time thing,” but while DePaul has been able to offer a salary pool between 2 and 3 percent most years, salaries were frozen for the fiscal year beginning July 2014 as well.

During the Q&A portion of the town hall, longtime psychology professor and Director of DePaul’s Center on Community Research Leonard Jason asked Bethke about the risks of having such a conservative budget moving forward. Jason expressed concern about the strain that may put on programs trying to be more competitive.

Data from IRMA.

“I think if you make budget cuts you are having fewer resources that have been available,” Jason said. “If at the same time you want to grow programs and bring in new students, that’s going to put a little bit of a strain on programs.”

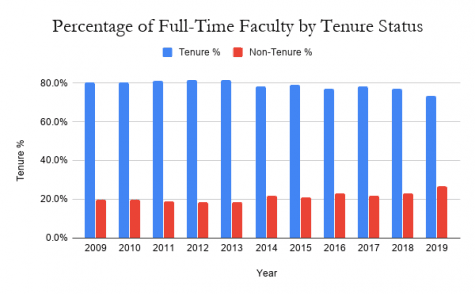

In the psychology department, which is home to about 4 percent of DePaul’s student body, Jason worries a tighter budget may limit the resources that makes DePaul attractive to psychology students, particularly tenure faculty.

“It’s kind of like there’s an intellectual richness that’s available for having people who have a tenured track — in other words, they’re here for a long period of time,” he said. “If you replace people with folks who have a one-year contract they don’t have the capacity to set up the types of research labs to give undergraduates the training that they need and to be competitive with our sister institutions that have those vibrant labs going on.”

DePaul has seen a reduction in the number of full-time faculty, particularly over the last three years. In 2009, just over 80 percent of full-time faculty at DePaul was tenured or on a tenure track. In 2019, that number was less than 74 percent. Last June, the university offered buyouts to all tenured faculty at least 62 years old with more than 10 years of service.

Data from IRMA.

“The thing that was encouraging to me is that he was talking about a campaign,” Jason said. “A campaign to bring in, you know, lots of money — hundreds of millions of dollars. And that’s exciting.

“But I think the thing we want to be careful about as we are trying to bring money in and are trying to get that endowment to a billion dollars, we want to make sure we don’t do anything to put at risk exemplary programs that have been created over the decades.”

Ahmed Zayed, who chairs DePaul’s mathematical sciences department and is a member of the faculty council, asked Esteban where he stood on the creation of a faculty union. While Zayed told The DePaulia he’s not in favor of a faculty union himself, he thought it was worth bringing up in the face of the salary freeze, which could prompt a stronger movement for a union.

Esteban said he does not have an official policy, but commented that “we’d prefer to work with people face-to-face rather than through an intermediary.” He did not suggest that he would fight the faculty council if they moved in that direction.

Zayed said a faculty union has some advantages, but on top of his feeling that unions can be anti-meritocratic, he worries that it may not be the best solution for a private university.

“If you form a union, there is a possibility of having a strike,” he said. “How would you feel as a student paying a lot of [money for] tuition, then one day you cannot go to the classroom because of a faculty strike?”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article stated that the 2021 budget will not include salary increases for faculty. That sentence has been amended to clarify that the 2021 salary freeze will impact all full-time faculty and staff.

Catherine Maxwell / May 9, 2020 at 9:17 am

This article should be updated in light of the pandemic shutting down on campus services. What are the new fiscal projections?

Georgina F / Feb 26, 2020 at 6:34 pm

I complete agree with Thomas. Why does it fall on the highest paid employees to decide who to discard? Those in leadership, especially Esteban and that goof ball leader in Advancement, should take salary cuts. Instead, I’m sure admins will be let go. People who do actual work. Esteban is cruising along thinking he deserves his salary. He should donate all 1M+ back of his salary to the university for being worse than useless.

Good grief!

Thomas Croak / Feb 24, 2020 at 4:48 pm

I am not surprised at the decline in the enrollment revenue. Leadership is the first casualty of progress and DePaul has suffered significantly in the last two year from that reality. No doubt there will be wholesale dismissals and terminations while the chief officers of the University vote themselves raises. Pathetic!