Representation of women in classical music sees increase, but overall imbalance remains

FILE- Katherine Baloff (right) performs with the DePaul Symphony Orchestra. The group rehearses three days a week for two hours, though only counts for one credit hour per quarter. (Kirsten Onsgard / The DePaulia)

“I have never thought of myself as a female trombonist,” said Megumi Kanda, principal trombone and one of two female brass players in the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra. “I’m a trombonist the same as anybody else.”

The classical music industry has endured a gender issue for centuries, with male performers, conductors and composers dominating the industry compared to their female counterparts — a trend that is slowly starting to turn tides.

The Women’s Philharmonic Advocacy, an organization promoting female representation in classical music, has completed studies covering the top 21 orchestras with the highest operating budgets in the United States over the past couple of years. The studies focused on what works orchestras are playing with specific emphasis on the composer’s gender.

Over the past four performance seasons, there has been a steady increase in female composers represented by these orchestras, with the most recent 2020-21 performance season having 99 works written by female composers out of a total of 855 works, totaling approximately 11.5 percent of all total works performed.

This is a significant increase from previous years which was at 8.6 percent in 2019-20, 4.9 percent in 2018-19 and 3.1 percent in 2017-18. While there has been an increase in the number of pieces performed by female composers in the past several years, over 88 percent of the pieces performed by major orchestras were written by men. The studies did not mention non-binary composers.

Female musicians have become more and more prevalent in United States orchestras — especially here in Chicago. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) was founded in 1891, but it was not until 1941 when Helen Kotas was appointed principal horn that a woman held a full-time position in the orchestra.

According to Eileen Chambers, the Communications and Public Relations director at the CSO, women now make up 40 percent of the orchestra, pointing towards the balance between male and female musicians improving.

The CSO became the first major orchestra to perform a piece written by a Black female composer on June 15, 1933, when they performed Florence Price’s Symphony no. 1 in E minor.

Brass instruments have fewer women in them; however, the 2020-21 Civic Orchestra of Chicago horn section was entirely female, but there are no female musicians in any other in any other Civic brass sections. Similarly, DePaul currently has no female brass players as part of their applied lessons faculty.

Kate Warren, horn player and lecturer of “Female Brass Players Don’t Exist,” and Kanda both believe that this imbalance will change in the coming years, considering the low turnover rate in orchestral jobs. Due to the industry’s competitive nature, some musicians stay in their job for decades versus the traditional three to five years.

“Orchestras are still populated by people, [predominantly] men, who won their jobs around that time period [late 20th century] and we won’t see a large turnover in the gender distributions of orchestras until that generation of players die out,” Warren said. “Not to be morbid, but in music, people tend to hold their chairs to much older ages than the average 9-5 worker would retire at.”

There hasn’t always been educators like Kanda and Warren taking initiatives to teach young female musicians.

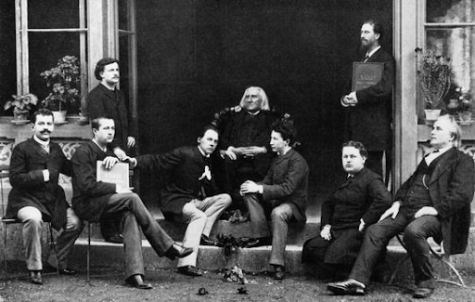

One of the first composers to ever take on female composition students was Franz Liszt back in the mid-1800s, which is fairly late considering that Johann Sebastian Bach died back in 1750. However, this was not met without it’s controversy. As shown in the image, Liszt has students of both genders; however, this photo was edited to remove his female students.

Warren and Kanda said that education is the solution to the classical music industry’s imbalance between male and female musicians.

“As with most things, perhaps the best way to effect change is through education,” Kanda said. “This means having equal opportunity at a young age for all genders and races to choose any instrument they want to play, without preconceptions.”

Kanda agreed with this sentiment, adding that music educators have a responsibility to teach beyond the constraints of gender roles.

“More specifically educating educators about how to break gender roles in the music classroom,” Warren said. “We can always look at it as a cycle but in my eyes training the next generation is step one in creating a more diverse workplace for musicians of the future.”

To listen to works by female composers, visit the CSO’s website for their playlist of works composed by women.