Frank Bubla, a former DePaulia editor, was among the 450 student demonstrators who illegally occupied the Schmitt Academic Center in 1970.

Led by the Black Student Union, hundreds from the DePaul student body gathered to protest President Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, the ongoing Vietnam War and the Kent State Massacre.

“People say, ‘DePaul, no, not DePaul.’ Well, Last night a lot of people were saying, ‘Kent State, no, not Kent State,’” Bubla said in an official transcript of the rally displayed on the front page of the May 8, 1970, issue of The DePaulia.

Following the Kent State shooting, which left four demonstrators dead at the hands of the Ohio National Guard, responses throughout the country further ignited an already tense series of anti-war demonstrations on college campuses.

Students at Kent State, like many students across the country, were protesting against President Nixon’s decision to invade Cambodia. Violence erupted throughout many days of protest, leading former Ohio Governor James Rhodes to request the National Guard.

“I think it’s about time people start realizing that this can happen here and any place else in this damn country. … This school participates in the same (expletive) system that has produced what happened at Kent,” former DePaulia photographer Hank Denzler said at the rally May 5, 1970.

Various demonstrations against the war in Gaza on college campuses across the country remind many of the significance of student protestors.

Robert Cohen, a professor of social studies and history at New York University, says the core messages of campus protests have common themes.

“This movement and the anti-war movement of the ‘60s are both concerned with the use of U.S. military might,” Cohen said. “I would say that it’s similar in that you’re thinking about global affairs. You’re thinking about U.S. military might.”

But Cohen also identified key differences that set the pro-Palestinian demonstrations apart from anti-war movements of the past.

A glaring contrast is clear to Cohen: social media.

The accessible and constant newstream of the violence unfolding in the Middle East may mobilize students on campuses differently than previous student-led anti-war movements, Cohen said.

“Especially because of social media, which didn’t exist in the ‘60s,” he said. “It was on TV, but you had to go home. You had to put on the news. It wasn’t always in your pocket.”

Graham Piro, a fellow from the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), further emphasized the impact that social media has on the difference between protests on college campuses now compared to decades ago.

FIRE also has granted DePaul a “lifetime censorship award,” with the organization citing what the organization called DePaul’s “commitment to censorship.”

“You’re getting information from all over the place …. We’re seeing videos of these encampments and protests,” Piro said. “So we have a more firsthand account, and you can sort of get into the question of is increased transparency going to affect the way that institutions react?”

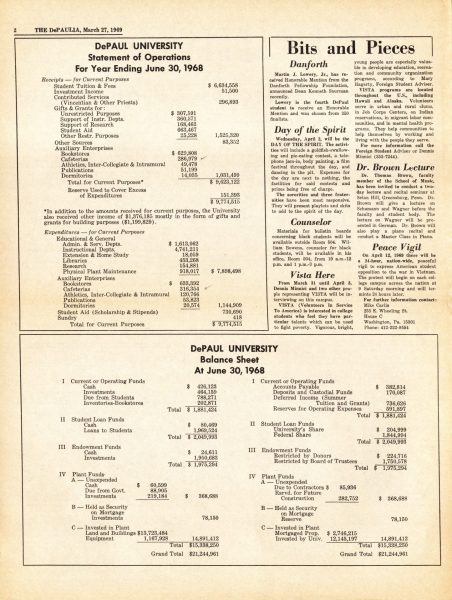

This difference is clearly visible in an ad in the March 27, 1969, issue of the DePaulia.

“On April 12, 1969 there will be a 24-hour, nation-wide, peaceful vigil to express American student opposition to the war in Vietnam,” the ad reads, citing an address and phone number for further inquiries rather than a quick social media post.

However, some protesting tactics have stayed the same on college campuses.

To Piro, colleges and universities have consistently been an environment for academic freedom, free speech and protest.

“Colleges and universities are places for open inquiry for debate for discussion for all these values, and protests are ways of students or faculty members voicing their concerns about specific issues,” Piro said.

On April 30, Columbia University student protestors occupied campus’ Hamilton Hall to continue their protests against Israel’s war on Gaza, a strategy long held by students at Columbia to protest the Vietnam War and apartheid in South Africa.

On Sunday, May 12, demonstrators at the “DePaul Liberation Zone,” DePaul administration said that “locks and chains” were placed on library entrances and windows.

This was eventually listed as one of the justifications for the police raid on the encampment on Thursday morning.

Former DePaulia staff member Bill Bike explains in the publication’s Sept. 29, 1978, issue that demonstrators occupying university buildings has been a tactic that existed at the university for over a decade.

“During the night, the protesting students took over the entire building and barricaded all of SAC’s doors,” Bike’s reporting of the 1970 anti-war rally reads.

For Piro, this often-utilized demonstration tactic can pose an opportunity for university administration or higher authorities to get involved.

He says that occupying buildings or barricading entrances may be considered “civil disobedience,” and certain free speech protections may not apply.

This is why Piro says it is important, especially for student demonstrators, to familiarize themselves with “the history of protest and also familiarizing yourself with your rights and what your university is going to protect.”

To some, university demonstrations aren’t as significant as some may think.

William Gordon, an expert of the Kent State shootings and author of “Four Dead in Ohio,” says that current demonstrations won’t have a lasting impact on foreign affairs.

“I do not believe the protests will change Netanyahu’s prosecution of the war or help bring it to an earlier end,” Gordon said. “College students can sometimes be full of themselves and deluded in thinking they can change the world.”

Protests on college campuses regarding the Israeli-Palestinian debate are also not isolated to our current environment, according to former issues of the DePaulia.

The first recorded coverage of Students for Justice for Palestine (SJP) at DePaul was published in a March 5, 2004, issue of the DePaulia.

“Struggles not foreign to student group,” former staff writer Matt Thromann’s headline reads

For many, it is evident that demonstrations on college and university campuses will continue, as they have for decades.

“We have the opportunity to change, let’s get on it, because if we don’t get on it, they’re going to be getting on us,” said James Hammonds, former BSU president, in a 1970 issue of the DePaulia.