Karina Gonzalez, 48, and her 15-year-old daughter were fatally shot by her husband, Jose Alvarez, in their Little Village home on July 3, 2023.

Before she was killed, Gonzalez had obtained a civil order of protection against her husband, which required law enforcement to remove his Firearm Owner’s Identification (FOID) card. But he never voluntarily surrendered his firearms to law enforcement, and the Chicago Police Department never removed his weapons either.

That loophole caused her death and the death of her daughter, anti-domestic violence advocates said.

Since her murder, lawmakers, advocates, survivors and their families have been working together to advocate for Karina’s Bill. The legislation would ensure that when a survivor of domestic violence has been threatened with a gun or believes that their abuser’s access to a gun is a safety threat, a judge can file a search warrant, along with the emergency order of protection, for those firearms to be removed.

But despite their efforts, the bill has been stuck in the Illinois General Assembly since May 2023. It must pass in the Senate to become law. There has been bipartisan concern about the logistics of enforcing this bill and whether it violates the constitutional rights of the person against whom the order is filed.

Rep. Maura Hirschauer, a member of the 103rd General Assembly of Illinois, is a lead sponsor of the bill. She said that policymakers are in negotiation with law enforcement agencies to draft safety parameters for this bill.

“It’s a dangerous thing to do, to go into someone’s house and confiscate their guns,” Hirschauer said. “We want to make sure we’re listening and making changes…and making sure they [police officers] have tools and technology to do it correctly, and also safely store the weapons.”

Donald “Todd” Vandermyde, a consultant on Second Amendment litigation and former National Rifle Association lobbyist, believes that this bill is not constitutional as it’s currently structured. He says that the bill allows law enforcement to remove the alleged abuser’s firearms before they’ve gotten the opportunity to plead their case in court.

“Then, they get a warrant. They take your personal property from you. They take away your rights to self defense [sic], and then it’s up to you to get a lawyer and go back to the court to do something different. It completely flips the entire system,” Vandermyde said.

According to Vandermyde, there is another potential problem with the bill. If law enforcement fails to confiscate all firearm parts and ammunition after the first search under an order of protection, the respondent could be found guilty of possession of a firearm if law enforcement finds more in other locations.

However, advocates say passing Karina’s Bill could significantly reduce the threat to the immediate safety of survivors of domestic violence.

“To me, that intersection between domestic violence and gun violence is so clear,” Hirschauer said. “I understand and respect our constitutional rights. But I also know that we can all agree that guns should not be in the hands of dangerous people.”

Megan Merrill, systems advocacy coordinator at The Network, an anti-domestic violence awareness group, said that Karina’s Bill “is really a technical fix” that would strengthen existing laws by ensuring that firearms are removed from people that a judge has ruled should not have access to them.

Anytime that a survivor of domestic violence takes action to challenge an abuser’s power and control, whether that be by leaving the relationship, filing for an emergency order of protection or applying for criminal charges, they risk retaliation from their abuser, Merrill said.

Olivia Basu, Senior Associate Attorney at Erin Wilson Family Law and former volunteer at Ascend Justice, regularly files orders of protection. She said Karina’s Bill could make survivors of domestic violence feel more comfortable when filing an order of protection.

“The matter of safety is a huge issue. It’s a reason why a lot of people don’t move forward on orders of protection,” Basu said. “I’ve had plenty of clients that want to get an order of protection and fill out all the paperwork, and then still don’t actually file it because they’re scared still of their abuser.”

While the bill has not yet passed, Karina’s death has inspired community members to band together. Baltazar Enriquez, President of the Little Village Community Council (LVCC), was there the night that Karina Gonzalez was murdered.

“There was a commotion on 26th Street, and we ran out to see what had happened. By then you had the police taping the area, and they were doing the investigation,” Enriquez said. “We didn’t know the details of what had happened, but we did learn about the incident the same day.”

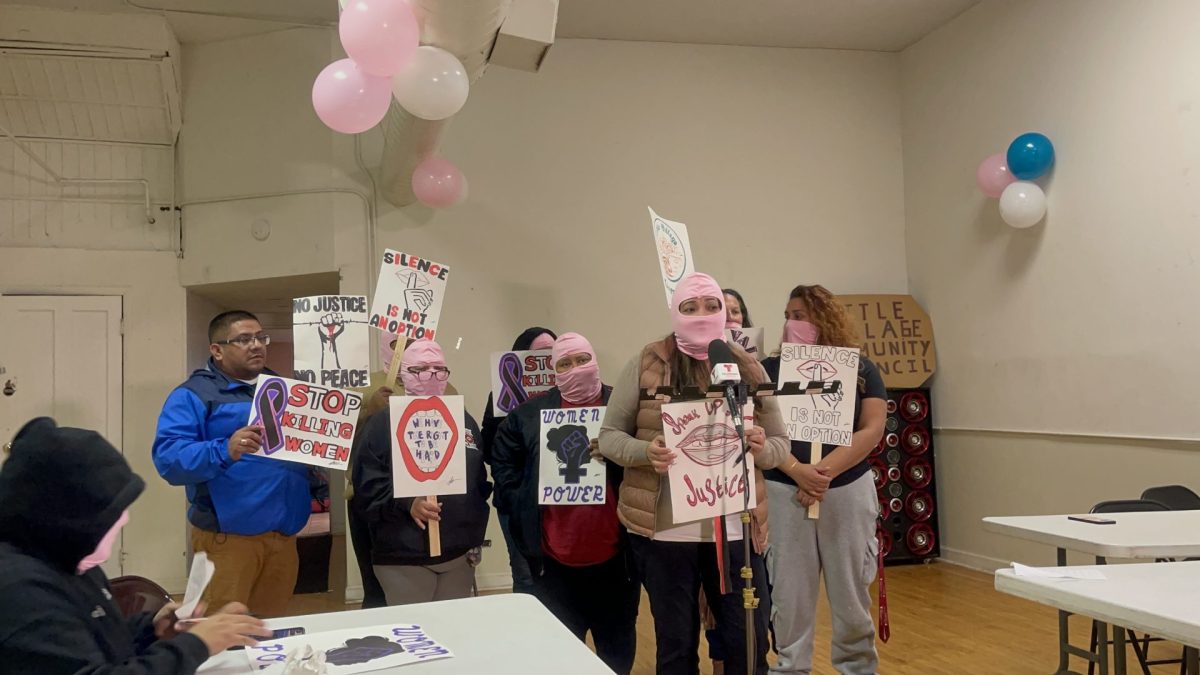

Enriquez helped to create a committee called Las Valientes that advocates for survivors of domestic violence. The group holds protests and rallies for women who were murdered in their community and beyond.

Members of Las Valientes wear pink ski masks while they march, as a symbol of strength and “freedom in anonymity.” The masks hide their identities, which is important as many of their members are also survivors of domestic violence, said Graciela “Chela” Garcia, a Las Valientes chair member.

Passing Karina’s Bill would create an opportunity for survivors to feel safe and have more encouragement in leaving their abusers, and it would help develop a “safer space for victims,” Garcia said.

“As a victim of domestic violence, I’d rather something effective be happening while I’m alive and in danger,” Garcia said.