OPINION: Queer imposter syndrome is a toxic mindset

Am I queer enough? Trans enough? A “real” member of the LGBTQ+ community? If you are part of the LGBTQ+ community, these thoughts have probably crossed your mind at some point. This is queer impostor syndrome.

“I found myself worrying about taking up undeserved space in the queer community — a community I deeply cared for, but didn’t yet feel like I belonged to,” writer Anna Levinston said in a personal essay about her struggle with queer impostor syndrome as a bisexual woman.

When I first saw the term “queer impostor syndrome,” I was quite confused.

Originally, I thought of the individual meanings of the words. An impostor is someone trying to be something that they are not. This led me to think “who would pretend to be in the LGBTQ+ community?” That alone sounds morally wrong on many different levels, so I took a look into it.

Impostor syndrome is the feeling of being inadequate despite proven success, according to the Harvard Business Review. It follows that in queer impostor syndrome, LGBTQ+ individuals are unsure if they are “gay enough.” The Harvard Business Review also mentioned that the “impostor” suffers from chronic self-doubt of their competence.

“From my observations, I’m not alone in feeling [of impostor syndrome],” said Point Foundation Scholar Eli Lawliet in his personal essay. “As queer folks, we’re at much greater risk for things like abuse, bullying, and other traumas. At the same time, we live in an often-hostile culture… one that doesn’t magically become friendlier simply because we’ve gained the right to marry or serve in the military.”

After looking at various essays and experiences from the Harvard Business Review, it is clear that queer impostor syndrome is a real thing that many people experience.

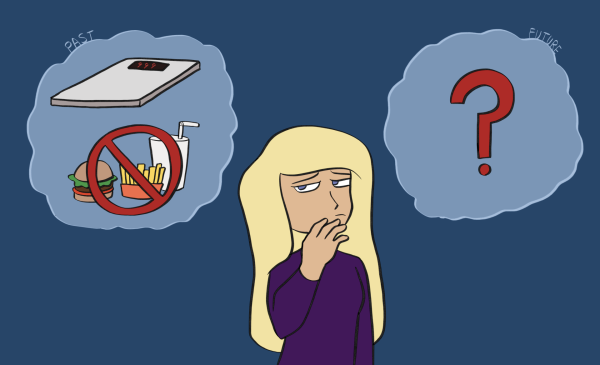

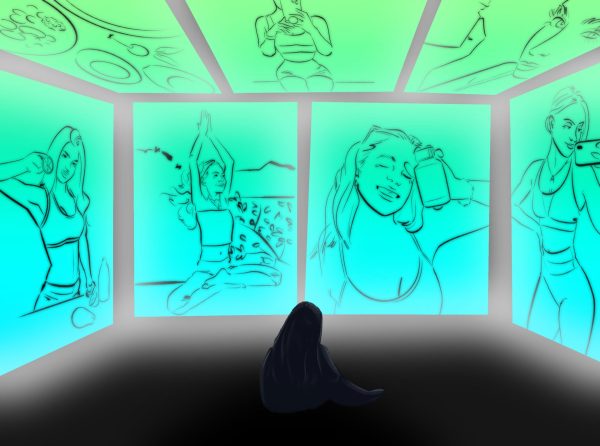

Now we’ve established that queer impostor syndrome is real. Queer impostor syndrome, to me, is the feeling of having to prove oneself as part of the LGBTQ+ community. This is due to internal conflicts with societal expectations ranging from the expectation of being straight at birth to fitting the stereotypes shown in movies and television shows. As Levinston said herself, “I found myself worrying about taking up undeserved space in the queer community.”

Queer sex therapist Casey Tanner supports the claim of society’s expectation of being straight at birth being a potential reasoning behind queer impostor syndrome. “Straight, until proven queer, so to speak,” Tanner said.

In my own life, I have struggled with queer impostor syndrome. I grew up in rural Wisconsin with nobody in the LGBTQ+ community around me. In fact, I was 16 when I met my first openly LGBTQ+ peer in youth orchestra.

When I came to DePaul, I thought I did not belong in the LGBTQ+ community because most the people around me came from areas where it was normalized and they already truly understood and found themselves — in ways I had not.

Luckily, I was quick to recognize my feelings of queer impostor syndrome by understanding that my experiences are no less than any other’s, and that I belonged despite my lack of exposure to the LGBTQ+ community.

Everyone has a different experience and a different way of expressing who they are as an individual. There is no specific way that anyone straight or a member of the LGBTQ+ community should act in order to feel validated by that community.

While queer impostor syndrome can be difficult to cope with, there are some ways that it can help a person discover more about themselves.

By recognizing my queer impostor syndrome, I learned new facts about myself. For instance, I love colorful shirts, especially with stripes, something that I never would have known without my queer impostor syndrome. That seems minuscule, but where I am from, that is considered out of the ordinary. Additionally, I discovered that I am not the biggest fan of Lady Gaga’s music, instead I prefer the music of Mahler or Tchaikovsky.

The moral is that one can use queer impostor syndrome by reflecting on their thoughts to discover their true individuality and sense of belonging—which (let’s be real here) is the sole purpose of the LGBTQ+ community.