A night in with two DePaul musicians

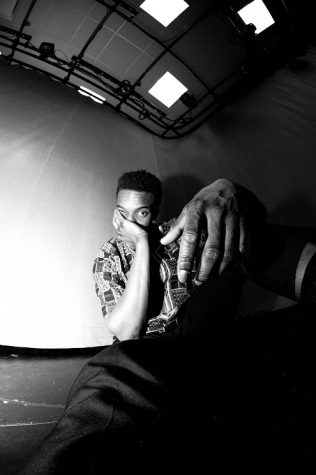

Muhamad Faal, otherwise known as Mo, (left) and Tyler Malone (right) have worked together through their time at DePaul making music.

On a chilly Tuesday evening, I lock up my bike outside of Mo’s place in Lakeview, make the familiar walk up to the front porch, knock twice and let myself in. Mo—real name Muhamad Faal— is on his way to the door. Over six feet tall with long arms and twists in his hair, he greets me with a big, goofy smile. “Hey! I’m so excited!” he exclaims and wraps me up in a hug.

Mo is an up-and-coming rapper from Edmonds, a suburb outside of Seattle, Washington. In a few minutes, we’re heading to the studio, where Mo produces the majority of his music. The studio is his friend/producer Tyler’s apartment in Buena Park. Still, I’m excited to finally see this elusive space where Mo and Tyler work several nights a week, churning out song after song.

Mo has been making music since he was eight years old. His latest single “Big Trippy” dropped on Spotify and Apple Music on October 30. His hip-hop style tends to lean toward the alternative side, bending the genre by tapping into sounds he grew up with: Gambian and Jamaican music. He says his main inspiration is the New York City rap scene’s ASAP Mob, as well Los Angeles’ Odd Future, particularly Tyler, the Creator and Frank Ocean. Most importantly, he draws creativity through friends, surrounding himself with fellow makers of art. He says he’s inspired by his environment, no matter where he is.

Today, 20-year-old Mo and his two roommates and best friends reside in a two-story coach house on Kenmore Avenue. Their small backyard is scattered with bikes and furniture found in the alley. The coach house boys even found a rocking chair for their front porch. They’re a resourceful bunch.

I follow as Mo puts the finishing touches on his outfit. He wears a striped black and red long-sleeve and thrifted high-waisted black bootcut jeans.

“Rate the fit,” he poses before me. I give him an 11.

Mo’s bedroom is decorated with posters, pictures, and hand-drawn artwork. One of the biggest posters reads “Illicit Music Collective” over a collage of familiar faces. Illicit was organized by Mo in January of 2019, comprising of acting majors at The Theatre School at DePaul University. Their work culminated in an album “Illicit Tape: Vol. 1,” and a raging house show in Irving Park last Valentine’s Day.

Mo’s family comes from Gambia, where he lived from ages 7 to 14. There, he began his rapping career.

“My sister would listen to hella R&B and write her own songs,” he says. “I would write my own songs too, and try to sing with her, and she was like, ‘Go do your own thing!’ So I was like, fine, I’ll be a fucking rapper. I started writing rap songs when I was 9, maybe 8, and I would just write really stupid rhymes.”

Back in the U.S. for high school, Mo’s passion for hip-hop continued.

“In high school, I started rapping with my two best friends. Our group was called RP3. It stands for Real People 3. Cuz no one else was real but us,” Mo says, flashing his goofy grin.

A full-length mirror with a broken frame leans against Mo’s wall, strategically placed so he can get one last glimpse of himself before he walks out the door. A prayer mat hangs above it. Mo doesn’t use it much — he hardly prays anymore, unless, he says, he feels like he’s run out of options. But Islam was once a necessary part of Mo’s life. In high school, his dad required him to pray five times a day. The mat symbolizes the Muslim, Gambian heritage Mo takes with him to Chicago.

***

We step into the brisk October night, and Mo asks me if I have an Allen wrench on me.

I laugh. “Why would I have an Allen wrench?”

“My bike,” says Mo. “The seat wobbles when I’m riding it. But it’s kinda fun.”

Before Tyler’s, we have an errand. “Tyler asked me to pick up eggs,” says Mo. “He always CashApps me like 30 dollars more than I spend.”

We fly down Sheffield Avenue, swerving cars and pedestrians through Lakeview and Wrigleyville. We stop at a bodega underneath the Sheridan red line, Alta Vista Foods. The clerk thinks Mo’s some kind of big-time rapper because he told him about his music. It’s funny, but I don’t blame the bodega clerk. Mo’s got this swagger and charm that’s ingrained in his artistry. Big things are coming.

Tyler Malone lives on the third floor of an apartment building on Sheridan Road. When we finally walk in the back door, Mo puts the eggs in the fridge and dumps a bag full of gummy worms and Hershey’s on the coffee table.

Tyler is slight and blonde, wearing an NYC Subway t-shirt and basketball shorts. He sits in front of his laptop, set up with speakers on either side. He pulls up a music video for a rapper that recently bought one of his beats. The video features at least four Lamborghinis. Mo bops up and down to the music.

“That’s a Lambo beat, bro! When am I getting one of these Lambo beats?”

The partnership between Mo and Tyler began through a mutual friend, Mo explains.

“Whenever I said ‘send me beats’ to any producer they only sent me one or two. Tyler sent me like, five. I was like, holy shit, alright, this is dope.”

As Mo speaks, Tyler plays a snippet of Ella Fitzgerald’s “Nature Boy.” Mo perks up and starts dancing around the room. His long arms fly through the air as he spins in circles on his tiptoes.

“Me and Tyler recorded for the first time in the beginning of sophomore year,” he says. “He sent me a bunch of beats to go to Gambia with and work over the summer after we met. I wrote a lot. I was in my sister’s old room, which is in the front of the house, and you get to see everything that’s happening… the kids playing outside, and anyone that would come in and out of the compound… the kids playing soccer over there,” Mo gestures, picturing the scene. “You had the breeze… it was the best part of my house. It was really nice writing there, I felt pretty inspired.”

At the end of that summer, Mo came back to the States to begin his sophomore year at The Theatre School.

“Me and Tyler linked and started recording. I brought my mic over, and he was like, I got the software, and we slowly learned how to record and mix.”

He pauses and hits the refrain of almost all artists today.

“The quarantine slowed shit down,” he admits. “But also, it was good for me, and for Tyler. We learned how to work from a distance together.” Mo turns to Tyler. “What do you feel like the quarantine helped with?”

Tyler looks up from his computer. “Quarantine helped me grow, personally,” he says. “I wasn’t able to make money off this,” he gestures to the computer. “I always loved doing this. Whenever I procrastinate with school, I make beats. Quarantine helped me, like, focus, and focus my life on — alright, how can I make this into something? And like, just being more responsible about shit, just being a lot more responsible about my life.”

“Yeah,” Mo and I agree in unison.

“And not being like, woo! I’m in college!” Tyler adds. We laugh. “Still workin on that… that’s important for me,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be important for other people, but it’s important for me.”

For the first couple months of the pandemic, Mo and Tyler stayed in touch using FaceTime, while Mo stayed in Chicago and Tyler went home to Long Island.

“It was honestly a sanity thing,” says Mo. “I saw Tyler every day last year… it was really hard, cuz I’m an extrovert. That also helped me grow, though. It helped me try to do things on my own, even though I was lazy about it… I started dabbling in producing.”

“He was trying to take my job,” Tyler mutters.

Mo laughs. “I’m hoping to dive into it more now. I got better at recording myself… I also got better charisma, what to do when I’m in front of a mic. It takes a while, like, just knowing how to use your voice on it to not make it too harsh. And I think now when I hear something’s off, I can clock that. So that’s been cool, figuring out the little things.”

Tyler keeps fiddling with “Nature Boy,” humming softly over the beat. The lyric, “And they — and they — and they —” repeats in a hypnotizing loop underneath our conversation.

In January 2019, Mo recorded at a professional studio for the first time.

“Oh, that was really fucking cool,” he reminisces. “I thought I was gonna go in there not knowing what the fuck to do, and the guy there was like, ‘Go in the booth and record.’ I did my thing in one take, and he was like, ‘This is your first time in a studio?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, but I’ve been recording with my friends forever.’ He was like, ‘You know how to do it.’”

Mo first learned how to record himself in high school. “I started recording myself on the Guitar Hero mic. And then I eventually leveled up: I stole a Blue Snowball from Value Village.”

“Blue Snowball?” I repeat.

“One of the most clutch USB mics. I couldn’t afford it ’cause it was 30 dollars… I was like bro, this is a Value Village, and I’m a charity case. So I just took it, and I started recording on that. I started working at Domino’s my senior year, made enough money to buy equipment, and I bought this cheap condenser mic, made my closet into a recording booth, and I would just record myself. I eventually recorded my first album. I called it ‘Senior Year,’” Mo says.

I listened to Senior Year when I met Mo three years ago and found out he was a rapper. Back then, he went under the artist name Moticulous. He changed his name to Mo in February of last year, along with the release of his latest album, “Moswrld.“

Mo’s not the most well-known rapper on the map, but his intentions with his music are unique and powerful.

“I’m not trying to project this hyper-masculine image,” he tells me later, as we sit and share a cigarette on his porch. “I want my music to reach people who were in the same place I was when I was growing up. You know, African, Muslim, queer kids. First-generation immigrant kids. Kids who are lost and don’t know where they fit in… I feel like I’m one of them who have really made it out, and I’ve been able to move away from those things that confine me.”

Mo has not arrived on the rap scene to project an inauthentic image of himself — he’s here to support and facilitate freedom. He’s showing up for expressivity, honesty, and individuality.

“It’s time to talk about me and my experience…. Not how other people made my experience,” Mo says as we head back inside. “The things that we think of as ordinary are so extraordinary, we just choose to look at it through a narrow lens.”

![DePaul sophomore Greta Atilano helps a young Pretty Cool Ice Cream customer pick out an ice cream flavor on Friday, April 19, 2024. Its the perfect job for a college student,” Atilano said. “I started working here my freshman year. I always try to work for small businesses [and] putting back into the community. Of course, interacting with kids is a lot of fun too.](https://depauliaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ONLINE_1-IceCream-600x400.jpg)