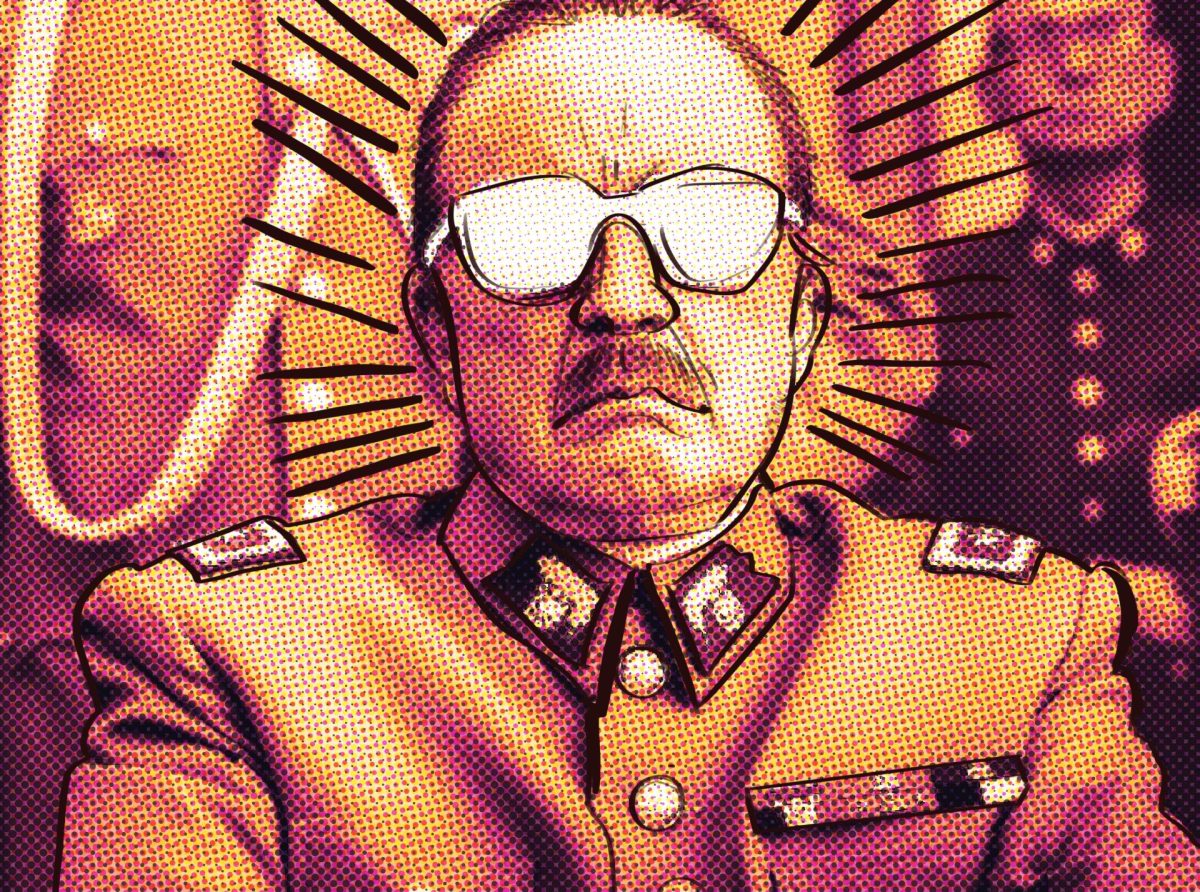

Something haunting, if not still comedic, about the film is watching an ancient, world-weary, vampiric Augusto Pinochet float above the modern streets of Santiago. The former Chilean dictator, adorned in his general’s uniform from decades before, spends his nights feasting on unsuspecting citizens. He ends his day by churning their hearts in dirty blenders to satiate his banal hunger. He may be gone from office and free from the limits of mortality but his avarice still infests the country and whatever family he has left at the end of his 250-year life. He wants to die. Everyone else wants him dead. But he just cannot seem to go away. His desire for power is inevitable. The greed remains.

Pablo Larrain’s “El Conde” is a steady piece of vampire fiction that strikes true thematically to Bram Stoker’s original critique of nobility. While it occasionally gets lost in comedic vignettes, the film remains a cynical yet beautiful ride down to the worst depths of humanity. In particular, it highlights how everyone who achieved great power, at the bare minimum, has to be a little bit evil.

“El Conde” stars Jamie Vadell as Augusto Pinochet, re-imagined as a vampire who has been kicking up chaos and political dissent worldwide since the French Revolution. After settling in Chile in the mid-1930s and faking his death (for the hundredth time), the dictator resigned himself to solitude in the countryside. Twenty years in exile later, he has finally decided to kill himself, sending his family, the Church and the mysterious narrator in a frenzy to scoop up every bit of him before he’s gone.

Cinematographer Ed Lachman, known for his frequent Todd Haynes collaborations, proves his mastery of the form in this modern gothic. The gorgeous black-and-white photography lets the right moments sit, helped by the fact that it was shot natively in that color palette (in contrast to many projects where a colorist will do it in post-production). As a result, the images create a depth that brings out the wonderful use of detail in Rodrigo Bazaes’ production design. Though it is set in contemporary Chile, the isolation from anything modern (outside of the image of the lord of evil represented by an old man in a tracksuit, which always gives me a chuckle) provides the film with a timeless quality, aided by the lack of color. The count’s den is a collection of ruins, the empty mountain air breezing through the cracks in the walls. His family is as emotionally vacuous as their surroundings; they surround themselves with the glamor of ages past, but they hold no value system to keep themselves grounded. The tinge of colorlessness robs their treasures of worth. The wind cuts through them like the paper-spined cowards they are.

Its agenda as a comedy can at times be a detriment to the overarching narrative. While momentarily entertaining, the cutaways to the children and the butler never grip or finalize themselves in a way the central story about Pinochet himself does. He and his relationship with the mysterious narrator (whose reveal I will not spoil but contains the best gag in the entire film) carries the disorganized narrative. The two’s back-and-forth inserts a sense of wit that pierces even the most cynical of audience members. Their presence in the narrative is what elevates this from a mildly entertaining but toothless comedy to a sharply modern satire on tyrants and the eternal nature of their greed.

“El Conde” resonates deepest when it features the titular despot. When it wanders, it becomes a series of funny but pointless asides to stories the overarching narrative does not explore enough. At the core, it is about the egomaniacs that value fleeting self-serving delights at the expense of the rest of us, and no matter how hard we try, they just cannot seem to go away. The names may change, but the ideals remain in a never-ending cycle of torment.

![DePaul sophomore Greta Atilano helps a young Pretty Cool Ice Cream customer pick out an ice cream flavor on Friday, April 19, 2024. Its the perfect job for a college student,” Atilano said. “I started working here my freshman year. I always try to work for small businesses [and] putting back into the community. Of course, interacting with kids is a lot of fun too.](https://depauliaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ONLINE_1-IceCream-1200x800.jpg)