After six days of negotiation between the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) administrative board and the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU), the Chicago teachers’ strike seemed to be close to ending on Sunday, Sept. 16-but the earliest students will be back in school is Sept. 19.

Karen Lewis, CTU President, told ABC 7 News she was optimistic about an agreement. However, at a press conference on Sept. 16, Lewis said union delegates would discuss the agreement further on Monday and Tuesday, citing a lack of trust between CTU and CPS. “Some of the language [in the agreement] isn’t right,” Lewis said.

According to a Chicago Tribune report, CPS presented the union with a revised contract proposal that included a restructuring of teacher raises, an appeal process for teacher evaluations and an agreement to freeze health insurance at current rates if union members participate in a wellness program.

CTU attorney Robert Bloch told the Chicago Tribune the union was “hopeful that we will have a complete agreement to present to the union’s House of Delegates by Sunday.” Similarly, Chicago Public Schools board president David Vitale said “the heavy lifting is over. The general framework is in place.”

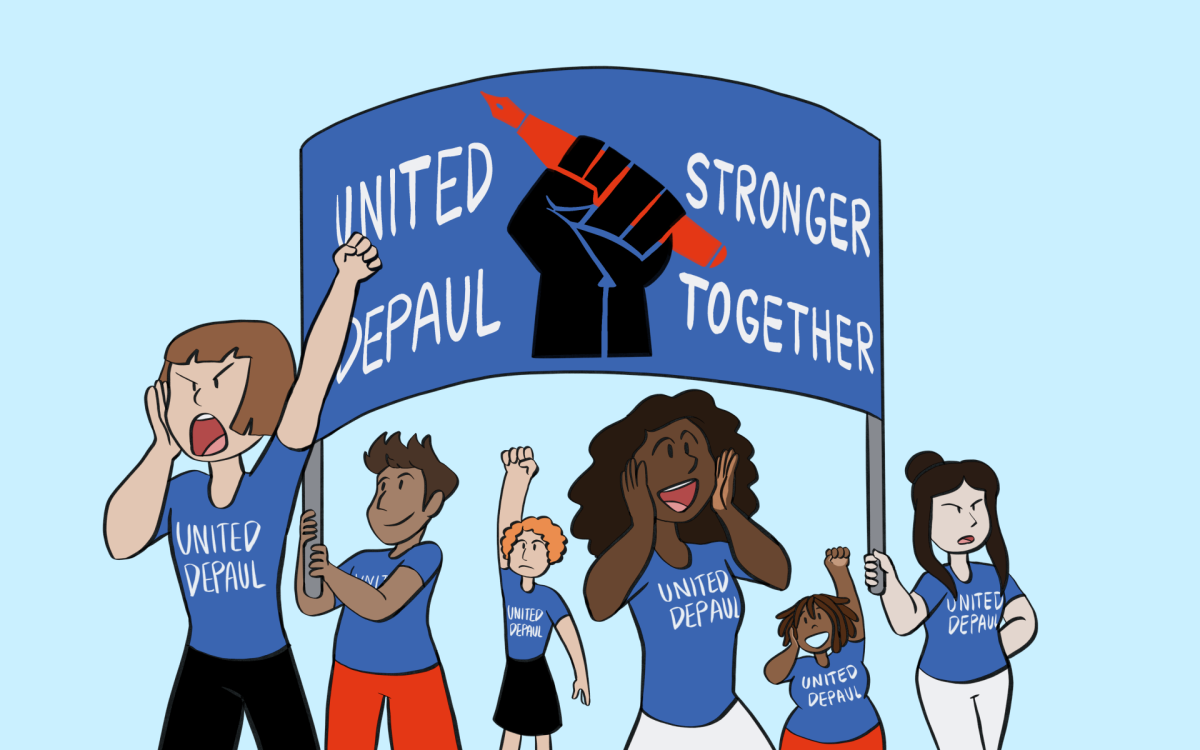

The end of the strike would mean that the nation’s third-largest school system’s 29,000 teachers and support staff would leave their posters on the picket lines to return to their classrooms, where around 350,000 elementary and high school students will once again fill the seats.

This turn of events came after teachers protested, marched and rallied at sites across the city, beginning on Monday, September 10, at Chicago’s City Hall. According to reports from police officials at the scene, around 10,000 striking CPS teachers protested in front of city hall, marking the first Chicago teachers’ strike in 25 years.

Wearing red t-shirts and holding posters reading, “Fair Contract Now” and “Attack Poverty, Not Teachers,” CPS teachers flooded the downtown intersection of Adams and Clark Street, banging drums and chanting, “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Rahm Emanuel’s got to go.” On the sidelines, a young woman held a sign above her head that read, “History class is in session.”

While teachers were demanding smaller class sizes, up-to-date textbooks, more social workers, better classrooms environments, disputes over compensation, teacher evaluation and job security, students were locked out of classrooms while the CPS administrative board and the CTU leadership were locked in negotiations.

“The city doesn’t realize how angry teachers are,” said Alicia Kostecki, a middle school teacher at Walt Disney Magnet School on Chicago’s North Side.

The city is no stranger to teachers striking. Chicago teachers last walked off the job in 1987, during a strike that lasted 19 days. Before that, teachers in the city’s public schools walked out nine times between 1969 and 1987 during periodic fights over salaries, working conditions and classroom environments.

The CTU strike has gotten mixed reviews from parents. A poll released by Capitol Fax and conducted by We Ask America found among 1,344 Chicago households, 56 percent approved of CTU’s decision to strike and 40 percent disapproved. While some parents have expressed anger about their children being out of school, others like hip-hop artist Rhymefest, see the strike as real-life lesson for children.

Parents are not the only ones critical of the strike; local and national politicians have chimed in, some adding support and others opposing the walkout.

“I am disappointed by the decision of the Chicago Teachers Union to turn its back on not only a city negotiating in good faith but also the hundreds of thousands of children relying on the city’s public schools to provide them a safe place to receive a strong education,” Romney said Sept. 10 during a press conference in Ohio.

“Teachers unions have too often made plain that their interests conflict with those of our children, and today we are seeing one of the clearest examples yet.”

Since the beginning of the strike, Lewis has remained firm in her belief that the strike was a necessary tactic.

“This was a difficult decision and one we hoped we could avoid,” said Lewis at a press conference on Sept. 9, the eve of the strike. “We must do things differently in this city if we are to provide our students with the education they so rightfully deserve.”

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel disagreed with Lewis, saying the strike and closure of CPS schools was avoidable.

“This is a strike of choice,” Emanuel said at a press conference on Sept 10. “The issues are not financial.”

The central issues debated between the CPS and the CTU included:

ξ

Salary

ÎàCPS offered a 16 percent average salary increase over the next four years.

ÎàCTU agreed the two sides were not far apart on compensation, but said they were far apart on benefits, and the CPU wanted to maintain their existing health benefits at existing rates.

Job Security

ÎàCPS offered new opportunities and security for laid off teachers by giving teachers the option to be placed in a reassignment pool for five months or electing to receive a three-month lump sum severance.

ÎàCTU said that it fears that if the Chicago Public School Board decides to close more schools, teachers would be displaced. The union demanded that laid-off teachers with acceptable ratings have firm recall rights.

Evaluation

ÎàCPS intended to institute a new teacher evaluation system named “REACH Students,” and proposed a plan to work jointly with the CTU on the implementation.

ÎàCTU had reservations about “REACH” as it factors in student achievement on standardized tests to evaluate teachers. Lewis said in a press release that after the initial phase of “REACH,” 6000 teachers, or nearly 30 percent of CTU membership could be discharged in one or two years.

ξ

Though the first two days of the strike showed little progress, the tables turned on day three. The CTU leaders and the CPS administrative board were ready to bargain.

“We made significant progress on the teacher evaluation side of the equation,” CPS Chief Education Advisor Barbara Byrd-Bennett told NBC Chicago. “Clearly we’re remaining consistent with not wanting to lower the standards for our children…I think there were really good discussions.”

Dr. Sonia Soltero, chair of DePaul’s Leadership, Language and Curriculum Department in the College of Education, was among the groups concerned about the new practice of using students’ standardized tests results to evaluate teacher performance.

“The annual test is neither fully reflective of students’ academic progress, or of teacher effectiveness. There is significant amount of research that points to this,” Soltero said. “There are many factors that are out of the control of teachers and schools related to poverty that affect students’ academic achievement.”

The group of educators sent a letter of concern to Mayor Emanuel and the Chicago School Board in March:

“Teachers will subtly but surely be incentivized to avoid students with health issues, students with disabilities, students who are English Language Learners, or students suffering from emotional issues,” the letter states.

The letter goes on, noting that “the dynamic between student and teacher will change. Instead of ‘teacher and student versus the exam,’ it will be ‘teacher versus students’ performance on the exam.”

In a recent interview with WGN-TV, David Vitale, President of the Chicago School said the board had made a number of proposals to the union in response to concerns, but the board is obligated to use test scores for teacher evaluation.

“The state law requires us to include test performance,” Vitale said.

Marc Wigler, an adjunct faculty member in DePaul’s College of Education and 18-year veteran CPS employee, said the risk for teachers begins in the evaluation plan’s second year.

“Teachers can be discharged without any recourse,” he said.

Lewis has sharply criticized Emanuel and his evaluation plan, noting that standardized tests do not take into account the outside factors teachers have to deal with in the classroom, including problems at home, inner city poverty, hunger and street violence.

Union officials said they fear more than a quarter of CPS teacher could lose their jobs if they are evaluated based on the tests, which Chicago students have performed poorly on compared with national average, especially in reading, math and science.

“Evaluate us on what we do, not the lives of our children we do not control,” Lewis said in the announcement of the strike.

Nate Marshall, an alumnus of Whitey M. Young Magnet High School on Chicago’s Near West Side, took to Twitter to express his support of the CTU strike, addressing the social issues CPS teachers deal with every day that are not accounted for in test scores.

“The strike is warranted. We’re already going to play at a deficit because we have social issues and challenges that other school districts don’t have because we’re a big city,” Marshall said. “It does to me, seem volatile to grade a teacher on test scores. It should be a part of it because that’s they way we evaluate our education system and its effectiveness, but there has to be more holistic approaches.”

Although Marshall said he thought students could benefit from seeing teachers stand up for themselves, he still hopes a resolution is imminent.

“I think there are times that you have to deny the immediate benefit for the long-term benefit, but I do hope my little sister can go back to school soon,” Marshall said.

Ida Mendicutti, a first grade bilingual teacher at Mary Lyon Elementary School in Chicago’s Belmont Central neighborhood, said the teachers’ strike would benefit students in the long run.

“I know we’re not going to get everything that we want, but I’m hoping that what we do get helps. It will be not only for the good of the teachers but for the students,” Mendicutti said.