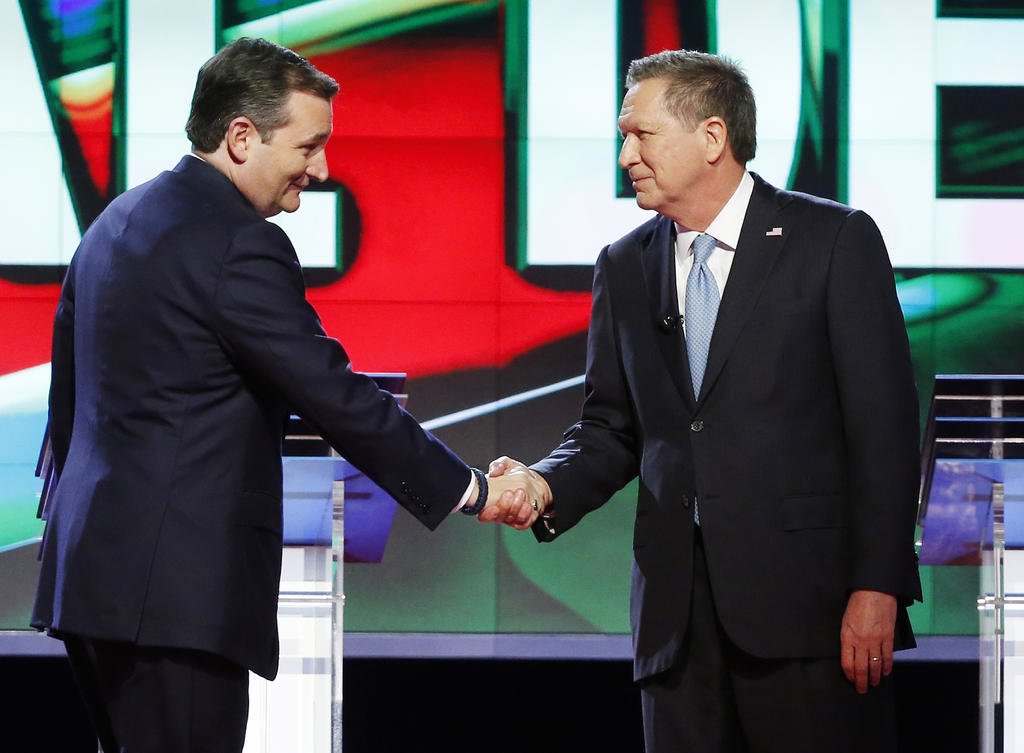

Ted Cruz and John Kasich announced a coalition to win more delegates than Donald Trump last week, then downplayed the alliance after Trump swept the April 26 primaries in New England. Though destined to fail, their last ditch attempt to stop Trump adds a new layer of desperation to the May 3 and 10 primaries in a race unlike any before.

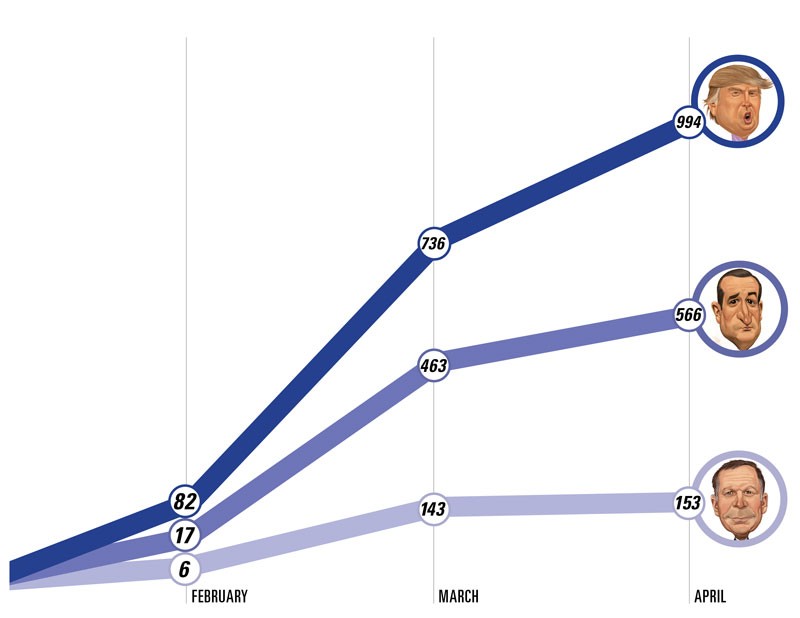

“I think it will fail as quickly as it starts,” DePaul political science professor Wayne Steger said. At the time of their announcement, Trump was closest to the 1,237 delegate benchmark needed to secure the Republican nomination with 845 delegates. Though both candidates denied any alliance later in the week, they said they would focus their campaign resources in particular states like Indiana and Oregon, where they hope to increase the number of votes for the non-Trump candidate.

Before they could test out the strategy however, Steger said the alliance would inevitably be ineffective. Moderate Kasich supporters would likely not vote for Cruz over Trump, and vice versa for the Evangelical Christian base supporting Cruz.

“They both recognize, especially Cruz, that (they’re) not going to do well in New England,” Steger said. “Indiana is a high priority for (Cruz), with a very large and substantial Evangelical population among Midwestern states.”

Oregon, on the other hand, is the target for Kasich, Steger said, where there is supposedly a large population of moderate Republican voters — though Steger also clarified the moderate perception is more of a misnomer because only three counties are more moderate while the rest of the state is conservative.

Regardless, the strategies seem to have come too late. There are only two months of primaries left and 583 delegates remaining. Currently Trump holds 996 out of the 1,237 needed to secure the nomination.

And beyond simply failing as a strategy, Cruz and Kasich working together against Trump only fuels Trump’s clearest platform: being the anti-mainstream candidate.

“This move feeds into a narrative Trump has been emphasizing lately: that the Republican ‘establishment’ is attempting to rig the primaries to keep him from winning the nomination and, by extension, to deny the will of the voters,” DePaul political science professor Erik Tillman said.

Emphasizing an alliance targeting Trump, Cruz and Kasich unintentionally fueled Trump’s media coverage. Immediately following their announcement, Trump mocked their “desperation” in a tweet that received nearly 29,000 likes and over 12,000 retweets.

“This is the campaign to illustrate that campaign spending doesn’t determine the winner,” Steger said. According to the New York Times, as of February, Trump only bought $10 million worth of media coverage, while receiving almost $1.9 billion worth of free media coverage. Jeb Bush spent the most in media coverage at $82 million, but dropped out of the race Feb. 20.

But the Cruz-Kasich alliance alone shows more than just a failed attempt to beat an unlikely opponent. First of all, alliances like it are a rarity in U.S. history. Most of the time, they occur in Europe.

“In Europe, various forms of pre-electoral alliances are fairly common in countries where the electoral rules make them necessary,” Tillman said. “The best comparison is in France, where there is a two-round system of parliamentary and regional elections. Parties will strike bargains in between the first and second round — in which each party agrees to strategically withdraw its candidate in certain districts in order to allow the other party to win, and vice versa.”

The last time a notably comparable alliance was made between candidates in the U.S. was in the 1964 election, David Woodard, a history and political science professor at Concordia University, said.

“Republicans tried to defeat Goldwater by getting all the candidates to skip or stay-out of the California primary and urge their supporters to vote for Nelson Rockefeller,” Woodard said. “It didn’t work and Goldwater won the nomination. He was crushed in November by Lyndon Johnson.”

Steger and Woodard named 1972 and 1980 as other examples; and although political machinations occur all the time, this is the first time a deal was publicly announced, Woodard said.

“In reality, these sorts of things have happened before,” Woodard said. “But this is an odd year where strange things are happening — so unprecedented events are not a surprise.”

But alliances often don’t work, Woodard said. The problem often comes down to political egos.

“Most candidates think they have a chance, even when it is clear to all of us that they don’t,” Woodard said. “So many candidates are hesitant to step aside — even in one primary state — for the good of an opponent. They might try to get something in return.”

Woodard said this could mean a cabinet post, paying campaign debt or media access. “In this instance, did Kasich get anything in return from Cruz? We won’t know for a while.”

Until then, Cruz and Kasich fight for legitimacy in a race dominated by one of the most unpredictable candidates for U.S. president.