How ‘Peter Rabbit’ teaches kids to save the planet

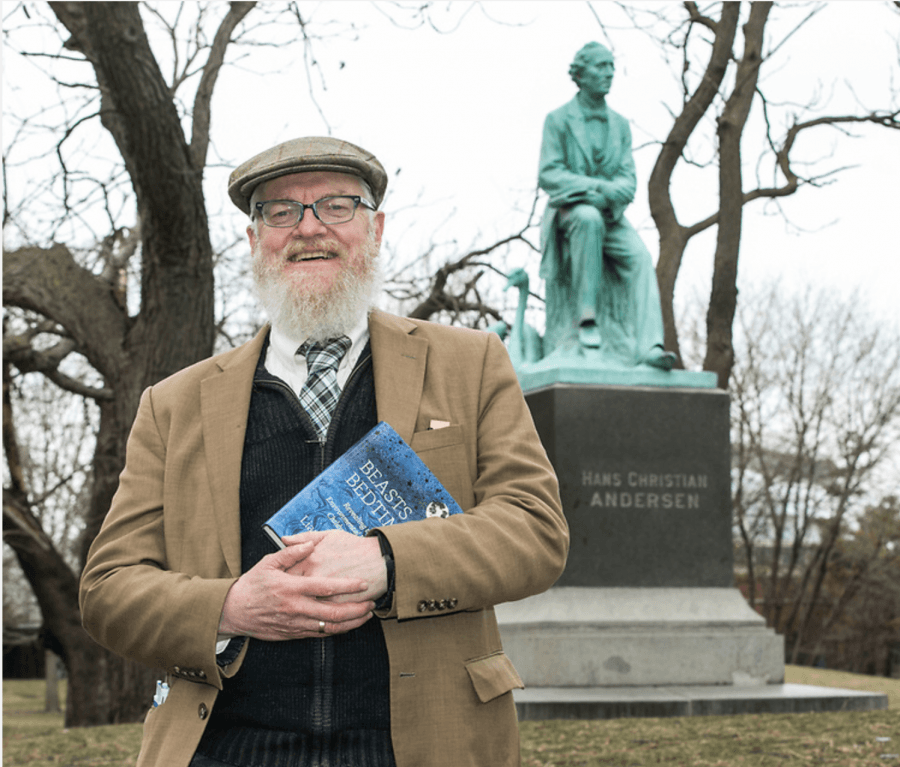

Liam Heneghan examined children’s books’ role in teaching kids about environmentalism.

When DePaul environmental science professor Liam Heneghan’s children left home for college, he thought of how he had managed to raise such dedicated, concerned young adults who care deeply for the world around them. The answer — children’s books.

All of these books personify animals in order to tell a story, but they keep children focused on the text. Children’s literature can instruct kids on a variety of topics, and with the release of his new book “Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children’s Literature,” Heneghan aims to show how they can teach children about their environmental surroundings too.

“I think there’s a general recognition that, in order to confront the problems of the future, kids need to have a firm education in environmental issues,” Heneghan said. “In terms of environmental literacy, I think the kind of most important thing is to ensure that children care.”

That includes books ranging from classics like “Peter Rabbit” and “Doctor Dolittle.” Far from being mere picture books, these works can actually have a vital impact on the way in which young minds understand the natural world around them.

Heneghan’s idea to write his book wasn’t a process that happened overnight. It took him 18 months in total to write, with five years of planning beforehand. In March 2013, Heneghan wrote an article for Aeon, a digital magazine covering culture and philosophy, titled “The ecology of Pooh,” which Heneghan described as being his “first meditation on the topic of how children’s literature embed environmental themes.”

Heneghan’s two biggest influences in publishing the book, he says, were his professional work as an environmental scientist and his two children leaving home for college.

“I’m kind of an environmental scientist that’s reaching out to children’s stories just providing kind of a road map to parents and guardians about … how much there is in that literature. That’s the idea,” Heneghan said. “Literature has always played this role in cultivating the minds of young people.”

Over the course of Heneghan’s career, he has mainly worked on issues surrounding biodiversity laws and conservation. On a local level, he partners with numerous area forest preserves and a variety of landowners to help them look at how they can better protect Chicago’s woodlands, wetlands and prairies. Heneghan has also been involved in issues related to invasive species and management.

Heneghan says that when his children left home, he began to reflect upon the effectiveness of the literary environment he had created for his two kids by way of the books he read to them as kids. Now adults, Heneghan described them as people who are “engaged in the world and interested and literate and empathetic and caring to animals and interested in the future.” As he reflected on his own children, he thought of how other children could similarly grow up to become well-rounded, environmentally responsible citizens who love the world and other people. He ultimately realized that literary reflection plays a vital role in developing those traits.

“The book really then aims to show that the books that kids are already gravitating towards have a lot of environmental literacy embedded in them, but embedded kind of an organic way — stories that kids actually want to hear rather than … specialized books warning about the parallels of climate change (and) global warming,” Heneghan said.

While environmental literacy is portrayed in the book as being important to children gaining global awareness, child literacy itself serves as an important stepping stone in early childhood education, according to Roxanne Owens, department chair of teacher education and associate professor of elementary reading at DePaul.

“Children’s literature is key to a child’s education,” Owens said in an email. “Books help with everything from child-parent bonding, to early language development, to learning simple concepts at an early age, shapes, numbers, letters, to more complex topics at later ages, history, science, mathematical concepts. Books also help children learn more about themselves as well as helping them learn about the world around them.”

Marie Donovan, director of DePaul’s Early Childhood Education Program, believes that Heneghan’s book adds another dimension to expanding how environmental education can be taught at a young age, and she hopes it will lead to more research in the future.

“Where I don’t see the literature moving just yet — and I think (Heneghan’s) research will go a long way in making this happen — is in incorporating environmentalism as yet another virtue one should aspire to owning, something that’s attainable and part of living a good life,” Donovan said. “Children learn better when they can connect with a character, and can see how that character is living her or his life. We need more books that contain settings, characters, and life lessons that model for children how to be natural, authentic environmentalists.”

Even though “Beasts at Bedtime” has only been on the market since May 15, Heneghan hopes that it will encourage not only parental-child conversations of environmental literacy, but also holistic conversations of literacy moving forward.

“Specifically what I want out of this is that parents will kind of recognize that the stories that they’re reading to children have a lot more important messages in them than perhaps they realized, and that it can hopefully promote conversations about favorite books that otherwise wouldn’t occur.”

Zain • Jun 21, 2018 at 5:35 am

I used to suffer from HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS for about 3 years. No medications or treatments ever really did anything for me (i tried them all no one work. but I was actually able to completely cure HERPES naturally after countless hours of online research. What worked for me is as follows: I saw Dr CAMALA Information online that he normally cure and treat disease and infirmities with his Herbal Medicine, I never really believed the people who where recommending him thou i saw on blog about 6 people where also testifying on how they were cured by Dr CAMALA, and still Ellen recommend Dr CAMALA who uses herbal medication to cure HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS and gave me his email, so i mail him He told me all the things I need to do and also give me instructions to take, which I followed properly.Before I knew what is happening after two weeks the HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS that was in my body got vanished. so if you are also heart broken and also need a help, . if you are infected with any disease like HIV,AIDS, CANCER,HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS, or any other disease you can also be happy like me by contacting…..

Name: Dr.CAMALA

Email him: [email protected]

What apps Number: +2349055637784

I“m given you 100% grantee, soon as you have getting in touch

with Dr.CAMALA your problems will be solved accurately.

Thanks..