Misinformation regarding COVID, the election plagues social media

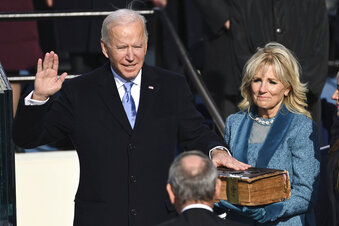

Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden, steps from his car as he arrives to board a plane at New Castle Airport, in New Castle, Del., Thursday, Sept. 3, 2020, en route to Kenosha, Wis. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Misinformation about the Covid-19 pandemic, election results and prominent figures impact how the average social media user understands these prevalent issues.

False headlines continue to plague social media as the internet continues to grow, allowing for falsehoods about key issues such as the pandemic and election to circulate.

“[Misinformation] can lead people to believe information that isn’t true, and therefore can affect their understanding of the world around them,” said Paul Booth, a professor of media at DePaul University. “It will give them false impressions of the world and make them believe things that aren’t true. But more importantly, it leads to a larger cultural confusion over the idea of ‘truth’ itself.”

The average user can become overwhelmed by the polarization of key issues, such as whether masks are effective against Covid-19.

Booth said this can cause disagreement among the public.

“When we don’t have a similar base of information to work from, we can’t agree on very simple things,” Booth said.

Social media channels such as Facebook and Twitter allow for false information to spread faster, according to associate professor Bree McEwan.

“It’s not like misinformation just springs from the social media environment,” McEwan said. “It’s just that the social media environment allows information to flow through the environment much faster.”

Facebook’s platform allows for groups to easily promote misinformation, according to McEwan.

“In fact, I think this is where a lot of the changes that Facebook is making to Facebook groups right now is they’ve figured out a way to access and build their own attitude online community and then push misinformation out,” McEwan said.

Some may fall prey to misinformation easily if the information they are consuming coincides with any biases they may have.

“Everyone kind of falls prey to disinformation in that particular way, when it can kind of close some uncertainty for us in a way that supports our confirmation biases that we already have,” McEwan said.

People who come across this misinformation have the liberty to verify it. But McEwan said that if the misinformation confirms someone’s bias, a question is raised: why would they fact-check it?

“On the other hand, the internet allows you to check some of this stuff much faster,” McEwan added. “Question is, Do you want to? Because if what you heard, it’s your confirmation bias, you’ve no reason to check it.”

False information can spread up to six times as fast than real news on Twitter, according to a PBS study.

“This information does not surprise me, because Americans tend to want to perpetuate biased ‘information’ that supports their ideas regardless of its validity,” said social media user Kelli Tosic, 18, of Lake Villa, in response to the study.

These falsehoods don’t appear out of thin air. McEwan said that misinformation can easily navigate through social media.

“It bubbles through the ecosystem first, and eventually kind of catches fire in a way the big thing,” McEwan said. “The video with the doctor that was like ‘Coronavirus is a hoax.’ I could see people who follow this information very closely give warning about this video before I ever saw it pop up in my Facebook feed because they were seeing it in spaces, that were these attitude consistent groups.”

Tosic said she has witnessed false information on the popular app TikTok about Covid-19 treatment claims made by President Trump.

“I saw a TikTok in July 2020 claiming that Trump did not encourage the American people to inject themselves with or consume cleaning products in order to ‘protect themselves against the coronavirus,’” Tosic said. “However, credible news sources, such as The New York Times, have reported that Trump did suggest that others do this, not to mention that he outright said to do so in an interview.”

Social media platforms are taking steps toward cracking down on misinformation by tagging posts that can contain it.

“Social media platforms have tried labeling information as false or even putting warnings on it,” Booth said. “They could certainly crack down harder by hiring more people to parse information and being more proactive about limiting the spread of false information.”

Tosic said she has noticed these efforts from social media platforms as well, particularly during the recent election.

“Throughout the 2020 Presidential Election, Instagram accompanied any post that contained information about or referenced the election with a link to live, valid election updates in case the post were to be false in any way,” Tosic said.

Booth said that the solution for misinformation starts with education.

“The best way to solve misinformation spreading is to teach more media literacy in schools,” Booth said. “Another way to solve this issue is for social media companies to take more responsibility for the spread of misinformation and the content on their sites.”