Activists and Chicagoans speak out against Lightfoot’s Victims’ Justice Ordinance

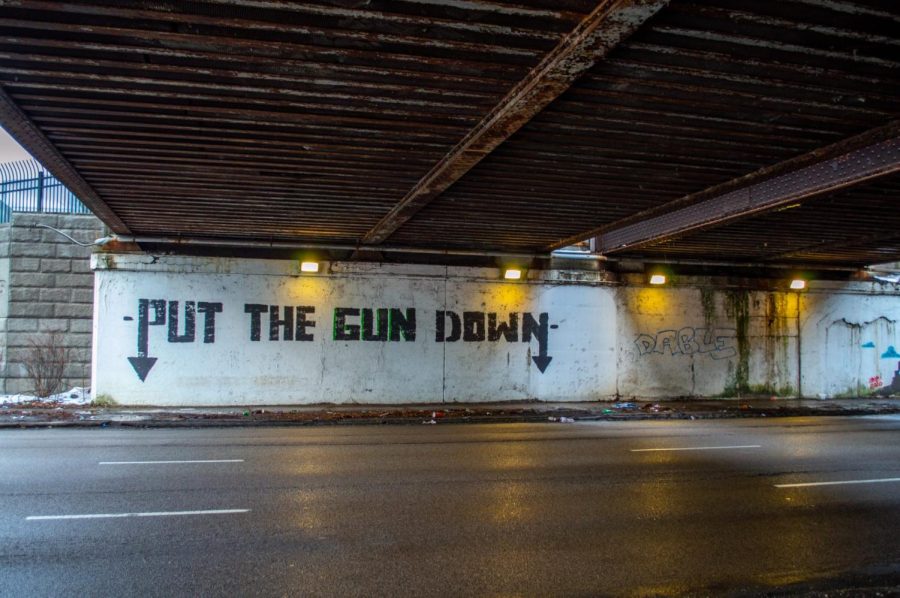

“Put the gun down” graffiti on the 600 block of Garfield.

When Mayor Lori Lightfoot introduced the Victims’ Justice Ordinance in September, activists spoke out against the proposal and her solution for decreasing gang violence in the South and West Sides of the city through civil asset forfeiture.

Lightfoot proposed the ordinance in response to the rising homicide rate in Chicago. It will allow the City to file a claim against any person who engages in criminal activity, and if found guilty, the City is permitted to recover “compensatory and punitive damages” with the goal of decreasing gang-related crime, according to the press release.

“It looks really great in a press conference, but it is not really something she’s going to deliver on,” said Edwin Yohnka, the director of communications and public policy at American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois.

“If we are successful, we will seize their assets and disrupt the financial lifelines that support this criminal activity and fuels their dominance in our city,” Lightfoot said in the press release.

The ordinance is modeled after the 1993 Illinois Streetgang Terrorism Omnibus Prevention Act allowing Chicago to file a civil complaint against streetgang members who knowingly engaged in two or more gang-related crimes within five years of each other.

DePaul criminology professor Xavier Perez said policymakers should recognize that urban unrest, racial injustice and the pandemic are the primary reasons for increased crime, rather than chasing policies of the past that were not effective in reducing crime or making communities safer.

“When you have economic incentives to policing, it leads to corruption,” Perez said.

If approved, it will give courts the authority to impose fines up to $10,000 for each offense and “a minimum of 50 percent of any monetary fines recovered will be dedicated to supporting victims of, and witnesses to, gang-related activity,” according to the press release.

“The problem is, what profits [from the forfeiture cases]? These are resources that would be awarded after lengthy litigation, and are there any profits after that?” Yohnka said.

Yohnka is concerned there will not be any profits from the civil asset forfeiture cases because there may not be any financial resources left to give to South and West Side communities once the litigation process has concluded.

The proposal does not define how it will give the profits back to South and West Side communities and does not say whether the money will be used for community reinvestment after it is confiscated from gang members.

Cori Wright, a current Hyde Park resident who grew up near 62nd and Sacramento, questions how the profits will be used to help underfunded communities with high crime rates.

“The community has the right to ask in what way?” he said.

Additionally, the difference between the original statute and the Victims’ Justice Ordinance is a shift in power from the elected Cook County State’s Attorney’s office to the unelected Corporation Counsel that is only held accountable by Lightfoot.

“The proposal itself is antidemocratic,” Yohnka said. “She is usurping power from an elected official for herself and for the person she has appointed.”

Critics argue the ordinance could have a negative economic impact on the communities it is targeting.

According to the ACLU, “The root causes of violence in Chicago communities are systemic policies of segregation and disinvestment leading to loss of jobs, opportunity and equity.”

Because gangs are integrated into the communities they reside in, it can be difficult to distinguish a gang member from victims or relatives. Yohnka questions whether innocent people could be collateral when gang member’s assets are seized by the City.

“The truth is, they actually won’t take assets from gang members, they’ll take them from their families,” Yohnka said.

Wright said his childhood babysitter, Pierre, was a gang member and had such an extensive criminal record that he couldn’t get a normal job to support his family.

Wright disagrees with the proposal’s solution to confiscate gang member’s assets because of his experiences growing up in both the North and South Sides of Chicago.

“He would have had to resort to finding a way by any means to put food in his kids’ mouth and to help his mom pay her bills,” Wright said in regards to Pierre’s case.

Organizations like After School Matters (ASM), who Wright was involved with as a teenager, work with nonprofits to provide teens with after-school activities that cater toward their creative interests. Wright believes investing in programs like ASM would be a beneficial way to keep young adults out of gangs and developing plans for their career and future.

“[Lightfoot] owes the community a decisive plan,” Wright said. “[She’s blocking] these people’s only source of income, or only source of staying alive.”

Wright believes by channeling the funding received from asset forfeiture into community outreach programs, after school programs, or into educational resources, Lightfoot could actively invest into South Side communities helping young people stay away from gang-related activities.

“Crime is a symptom of something else, and poverty, disinvestment in Chicago’s neighborhoods, housing segregation, all of those are principal causes of crime, but unless we are having real issues about that, then this is all just political theater,” Perez said.