What the Iowa caucus debacle means for the rest of the 2020 presidential election

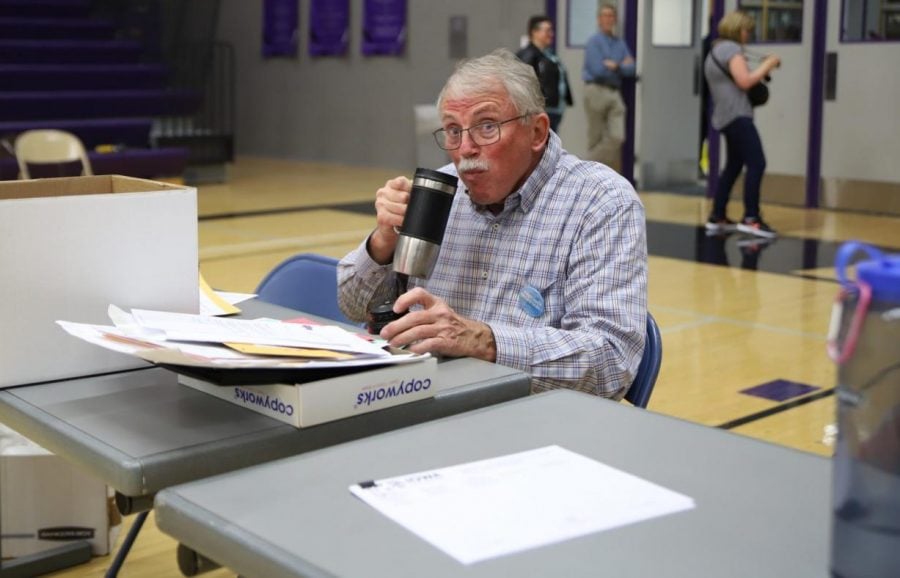

Jay Willems, a volunteer at the Mt. Vernon South precinct at Cornell College in Mt. Vernon, Iowa fuels up for a long night of caucusing Monday Feb. 3, 2020.

MOUNT VERNON, Iowa — The sounds of basketballs dribbling in the Mount Vernon High School gym fade as people trickle into the nearby cafeteria. The high school is one of Iowa’s 1,678 caucus precincts, at which attendees will help choose which presidential candidates will receive Iowa’s 41 state delegates.

The precinct’s results would be made clear when attendees aligned themselves with candidates – or chose to remain uncommitted – and snippets of results from other precincts would pop up on Twitter throughout the night.

It would be a long night waiting for results, but everyone would know before the morning. At least, that was the expectation.

It took almost 24 hours for the first results, with 62 percent of precincts reporting, to be released. Final results still weren’t in nearly 48 hours after the caucuses ended; 92 percent of precincts had reported results at that point. The Associated Press eventually announced Feb. 6 that it could not declare a winner because the leading candidates, Pete Buttigieg and Bernie Sanders, were so close together. Buttigieg received 13 of the state’s delegates and Sanders 12; both declared themselves the victors, Buttigieg saying so before any results had been reported.

Officials blamed the delay on coding issues with a new smartphone app, created by Shadow, Inc., that caused it to report out only partial data even though people were able to enter accurate results. Technology flaws were compounded by user error, as some precinct captains responsible for reporting results to the state party — many of whom are senior citizens — struggled to navigate the software.

As precinct captains abandoned the app to call in results manually, phone lines at the Iowa Democratic Party headquarters overloaded, delaying results further.

Calling what had happened “unacceptable,” Troy Price, chair of the Iowa Democratic party, told reporters before the first set of results were announced Feb. 4 that the party “took the necessary steps” to ensure the data was accurate. He said this was done “out of an abundance of caution.”

Despite circulating conspiracy theories, there is no concrete evidence the Iowa Democratic Party purposely withheld results, pushed any candidate’s campaign to victory or otherwise encouraged the chaos and uncertainty that followed the Iowa caucuses.

“Iowa wouldn’t benefit from fixing [the results],” said Ben Epstein, a professor of political communication at DePaul.

That hasn’t stopped discussions about taking away Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status, whether or not the results matter, or faith in elections generally.

As the first state in the nation to hold a caucus or primary each presidential election cycle, Iowa has been considered important for candidates’ momentum, endorsements and fundraising, as well as for giving the country its first glimpse into how the candidates will do with voters.

Historically, winners of the Iowa caucuses have much higher chances of getting their party’s nomination, Epstein said.

The results delay and ensuing chaos may have also helped the leading candidates, Buttigieg and Sanders.

“Both have been able to downplay little nuances,” said Nick Kachiroubas, a professor of public service management at DePaul.

For example, Sanders won the popular vote even though Buttigieg received more state delegate equivalents, which are similar to members of the electoral college at the national level. On the other hand, Buttigieg won in more counties than Sanders and also had more individuals switch to him in the second alignment than Sanders.

However, seeing an election that has been played up as extremely important may have hurt some people’s faith in elections.

“Even if you aren’t in Iowa, it causes you to go, ‘Well, if we can’t even get an election right…,” Kachiroubas said. “It can be enough for them to sit at home.”

Many Sanders supporters in particular do not trust the Democratic Party to give their candidate a fair chance.

Buttigieg’s campaign paid Shadow, the company that created the app that caused the results chaos, $42,500 for “software rights and subscriptions,” according to Politifact. The campaign had no role in the app used by the Iowa Democratic Party. Joe Biden and Kirsten Gillibrand, who has since dropped out of the race, also gave Shadow money.

#MayorCheat, a play on Buttigieg’s nickname, Mayor Pete, began trending on Twitter soon after the caucuses due to the campaign’s ties to Shadow and because Buttigieg claimed victory before any of the results were officially reported.

The Shadow app was rushed and wasn’t tested adequately, Epstein said.

“Innovations are exciting but not always good or helpful,” he said. “Innovation is not always good for innovation’s sake.”

Businesses, political parties and foreign powers all have interests in making sure technology benefits them, he continued.

“A paper trail and trusting the results of an election should be the most important consideration,” he said.

Nevada, the next state that will hold caucuses this election cycle on Feb. 22, has already abandoned plans to use an app similar to what Iowa had. Instead, the Nevada Democratic Party plans to use what it says “is not an app but should be thought of as a tool” preloaded onto iPads and distributed to precinct chairs, the Nevada Independent reported.

“We had already developed a series of backups and redundant reporting systems, and are currently evaluating the best path forward,” the party said in a statement Feb. 4.

There are plenty of Iowa voters who seem fired up enough about the election to participate again in November, despite what happened last week. Many care about the Democratic nominee’s electability when he or she faces Donald Trump, but they also care deeply about issues that affect their lives and about the kind of people their candidates are.

Juanita Andersen of Mount Vernon, Iowa, said she went to as many candidates’ events as she could before settling on Tom Steyer as her first-choice candidate.

“To me, Tom was the most genuine, the most sincere and he has the credentials to be able to do this,” she said. “Some people say, ‘Yeah but he’s rich and trying to buy his nomination.’ No he isn’t; he’s buying name recognition. Professional politicians who’ve been doing this for a long time, they have that already.”

She also said not being too progressive would benefit Steyer’s ability to win.

“This is the first time I’ve ever done this,” Andersen said. “…I am scared to hell for this country.”

Josh Lemon, 24, is a Coralville, Iowa resident who said he’s concerned about Trump’s rhetoric and attitude. Because of those concerns, he registered for the Democratic Party to be able to participate in the caucuses; he had always registered as an independent before.

“I couldn’t really say anything bad about [Trump’s] policies or anything,” Lemon said at a Buttigieg rally. “It’s just how he’s dividing the country.”

Lemon said if Buttigieg does not get the Democratic nomination, he plans to vote for Trump in the general election.

Graham Bradbury, 17, who will be 18 by the general election, was one of the few Andrew Yang supporters at the caucus at Mount Vernon High School.

“It’s pretty clear [Yang] might not be viable, but it’s important that we’re here for the end goal: who’s going to become president,” he said. “Just choose wisely on who you’re going to caucus for. Don’t necessarily go for who your family goes for or who you think is the leader of the party. We did that in the last election and we lost.”

As to what will happen to the Iowa caucuses, that remains to be seen.

Epstein predicts officials will simplify and streamline the process but will still keep it as a caucus.

For now, all eyes are on what will happen in New Hampshire, Nevada, South Carolina and beyond.

“It’s a long ride, but it’s always been interesting to watch,” Kachiroubas said.