A Seamless, Uninterrupted Action: Jim Duignan and Stockyard Institute

When Duignan looks back on his work its all been about people and community trying to help confront struggle in innovative ways.

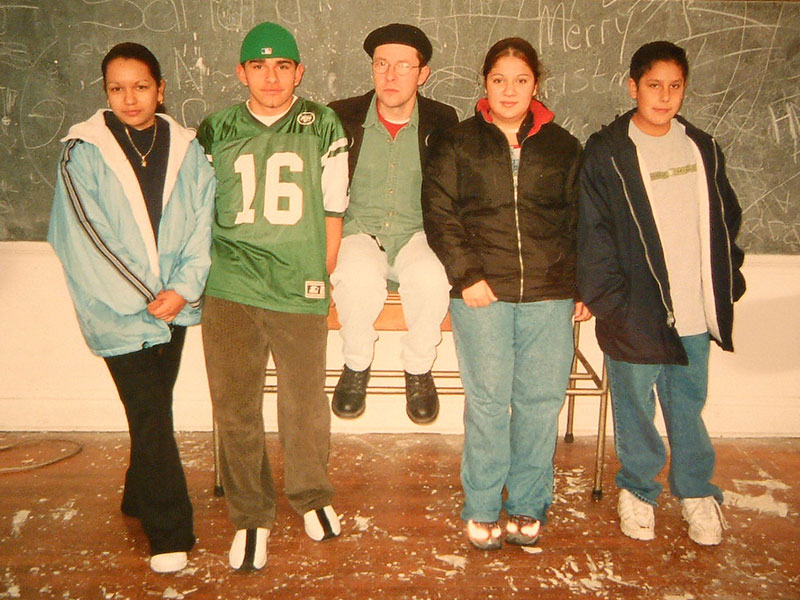

Jim Duignan is always in a conversation with himself. As an artist and an educator for nearly 30 years, Duignan’s mission has been one of filling gaps. What began as informal meetings with middle school dropouts in the Back of the Yards neighborhood transformed into a lifelong practice focused on a process of radical pedagogy. Duignan dubbed his practice Stockyard Institute, a deconstruction of educational and civic conventions.

Now twenty-five years later Stockyard Institute remains as when it began, an opportunity for learners to take control over their education and a vessel for Duignan to fulfill his own, socially conscious artistic vision and with a new retrospective exhibit on Stockyard Institute at the DePaul Art Museum, Duignan is taking the opportunity to look toward the future as much as he is commemorating the past.

Ask anyone who’s known Duignan for long enough and they’ll tell you his work is his entire life.

“I’m sure this started when he was like… seven,” said Rachel Harper, co-curator of the new exhibit. “I think he came onto the earth with this kind of orientation.”

Looking at Duignan’s story, his sense of purpose is hard to deny. Born and raised in Chicago, Duignan spent his early years feeling that school wasn’t built to address his needs. A bright and creative child who was constantly sketching and building in his free time, Duignan felt let down by his elementary school’s weak arts program and uniformed education.

“Those elementary school experiences were horrible, school didn’t provide a kind of platform for me to interpret my experiences well,” Duignan said.

Before high school, much of his creative energy needed to be through more unconventional means. He found one of his first true learning experiences in Boy Scouts, or what he affectionately refers to as his “nature school.” Duignan’s scoutmaster fostered his love for nature, and he was drawn to the raw materials of the forests, which he would use in endless building projects. Most importantly, Scouts was a place where Duignan and his peers could collaborate. As a young boy, Duignan found power in these types of spaces, where he and his friends could think, play and develop themselves outside of stifling schoolyards. Duignan developed a fondness for the playgrounds, parks and alleys where he and his friends gathered to simply be themselves, and build their own knowledge. These places held limitless potential for him, and they acted as the blueprint for what Stockyard Institute would become.

Duignan wouldn’t be able to properly exercise his artistic abilities in a school setting until his time at Taft High School, where his spirits were lifted by a bolstered arts program and a brand new art building. His outsider view on education would continue into his adult education. As he studied art at UIC, he became aware of radical leaders in pedagogy, the theory of teaching. Jane Addams of Hull House and Brazilian educator Paulo Freire were a few of the many scholars whose work appealed to Duignan. By 1995, when he was approached to develop an arts curriculum for a new middle school located in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood, Duignan already had a very clear idea of the pitfalls present in conventional schooling. With his upbringing, as well as a thorough arts education, Duignan sought unique ways to approach the issues of schooling in a more socially conscious and empathetic way.

The summer before the school was set to open, Duignan had the opportunity to meet with a group of local dropouts. He insisted on removing the children from the school space, instead locating their group in a nearby abandoned school. Initially, Duignan refused to teach the children, choosing to focus on his own work and allowing them free reign to discuss or engage with each other in any way they saw fit. Over time, this tentative grouping established a trust with one another. The turning point in their conversation came when one child admitted he feared being shot in the back on the way to school. This sparked a conversation among the kids, all of whom could relate to the fear on some level, and out of these conversations came the concept of the gang-proof suit. Over the next few months the idea of the gang-proof suit, a fictional suit of armor which would protect children from gang violence, was sculpted by these students, born out of conversations about real fears and problems facing the kids.

In Duignan’s eyes the group had evolved into a design collective. “I wanted to think about teaching art differently,” Duignan said. “Like why can’t we do projects just based on young people’s questions?” It was this idea, that young people should have a voice in the creation of their own education, that would become an important pillar of Stockyard Institute’s philosophy.

This initial project would grow into a lifelong practice. Duignan’s focus became letting learners find what traditional education couldn’t address and helping them confront it their own way. For Duignan, the school systems missed out on a critical human component of education, and rather than serving the individuality of each student, they sought to flatten it. After his experiment with the gang-proof suit, Duignan chose to continue on his path of transformative education, officially founding Stockyard Institute, which takes its name from the slaughterhouses once located in the Back of the Yards neighborhood. To Duignan, the fluid nature of Stockyard Institute is what makes it so unique. He discovers a learner’s needs, then gathers the resources, the support and the guidance to complete whatever project they can, “I orchestrate things, I put people who need things with people who have an excess” Duignan says. In this way, the process of the Stockyard Institute is very malleable, and often takes many shapes, but Duignan will always stick to his method of giving people the agency to explore their own needs. If you ask him, he won’t trump up his own role in the practice. “It’s not called Jim Duignan’s next art project,” he says. Duignan understands his role within Stockyard as that of an orchestrator, not a teacher or someone in charge, simply a person who gives others space. This lack of hierarchy is part of what makes Stockyard so innovative.

Now, after 25 years of practice, Duignan and Stockyard Institute are being honored with an exhibit at the DePaul Art Museum. The exhibit is a unique experience. The pieces are often less meaningful by themselves and more representative of a significant time or idea in Duignan’s practice, less an artistic feat in isolation, instead a series of totems commemorating the great artistic and pedagogical feat that is Stockyard Institute. Duignan insists that the exhibit is not meant to ruminate on the past, but to look forward to the future of the practice as it moves into the next 25 years. This is best seen in the radio station sitting at the center of the exhibit. Duignan and friends broadcast live every Thursday, communicating ideas live and in the moment, not commemorating a past artistic accomplishment but existing in the present and thinking towards the future, the exhibit stands as another example of a space Stockyard Institute has created to explore ideas and address needs.

When Duignan looks back on his work, it’s all been about people and community, trying to help confront struggle in innovative ways. Growing up in Chicago he saw the challenges that faced those living in the city, and constantly fought to fix them. “Jim’s practice is all about relationships and about being slow and really taking the time to listen, to get to know both people and places,” said Ionit Behar, assistant curator at the DePaul Art Museum.

Duignan hopes that by teaching and collaborating, both at DePaul and within his practice, he’s leading more people to be leaders of social change. He’s busy most of the time, always moving towards the next thing, approaching new people, looking for the next opportunity to create a new experience. Constantly dissecting the ways his community can change. For him a stagnant piece of art isn’t enough. It’s the constant motion of his work in Stockyard Institute that makes it so effective. Duignan describes his life as a “seamless uninterrupted action” — his work and his life are intertwined, one and the same, making him, and Stockyard, unlike any artist, person, or practice you will ever encounter.