‘Flamboyant, Gay, Man-Thing’: Nontraditional performers make space in Chicago’s drag scene

Drag queen Boots performs at Golden Dagger in Northalsted, commonly known as Boystown, as the crowd watches on March 5.

Chicago’s Northalsted neighborhood, commonly known as Boystown, is iconic for its wealth of talented drag queens that pile onto brightly lit stages and strutting in front of loving crowds.

The night starts with the queens folding their gowns, boots and wigs over their arms and piloting packed suitcases through dense crowds of drunken bargoers.

Then, the transformation begins: An everyday Chicagoan morphs into a regal, outlandish, or utterly camp being of radiance.

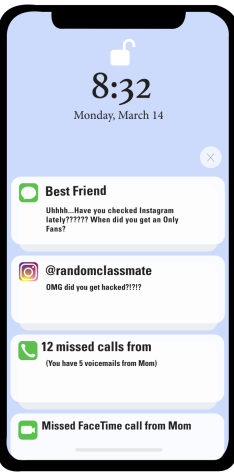

For nontraditional drag performers, Boystown’s drag scene is competition among white, cisgender, gay men for the money and approval of other white, cisgender, gay men. When drag is presented through this narrow lens, potential performers are turned away.

“There’s nothing wrong with mainstream types of drag, but I think it becomes an issue in terms of diversity,” said Madison Hill, a DePaul senior who moonlights as Georgia Rising. “A lot of people don’t feel included, because they’re nonwhite.”

Championed by gender nonconforming as well as lesbians and other queer folks, nontraditional drag allows them an opportunity to express themselves outside the boundaries of what we would constitute as traditional, pageant drag.

Carolina Aceves, known as Whorechata on stage, is a DePaul senior graduating at the end of March.

“It’s fun to be able to do drag, especially nontraditional drag where I could like be this like flamboyant gay man-thing,” Aceves said.

Aceves met many of their counterparts online and through Discord channels. Their hope is to create a community of nontraditional performers and push the boundaries of Boystown’s rigid drag scene.

“We’re trying to build a collaborative, horizontally structured drag house full of lesbians, nonbinary people and people of color to really make space for this kind of drag,” Aceves said.

Trying to get bookers on the rainbow-clad stretch of bars and clubs has been a tough task. So, these performers put on their own shows with other nontraditional drag artists.

“When I first met all of them, we decided that we wanted to put time and energy into putting on drag shows of our own,” Aceves said.

While some popular bars have been tougher to work with, Aceves and others found their spaces at venues like Golden Dagger, just north of DePaul’s Lincoln Park campus.

For Aceves, Golden Dagger is “one of the best venues in Chicago for lesbians, people of color, and gender non-conforming people.”

A lack of diversity in Chicago’s drag scene should be a wake-up call for bookers.

“For people that are a part of the LGBT community, especially lesbians, trans performers and people of color — there’s been a major lacking as far as our industry goes,” Zoey Victoria, a talent buyer at Golden Dagger, said. “Venues are finally waking up to the talent that’s in this city.”

Finding places to perform and make a living has been tough enough for nontraditional performers like Hill,committing time to the craft is another hurdle.

After months of doing drag and being a student, Hill still struggles with this balancing act.

“I was really nervous, because it takes me a long time to do my makeup,” Hill said. “I can’t have any homework. I have to dedicate as much time as possible.”

Hill’s counterparts know they’re a student, and sometimes that gets them in trouble.

“I made the mistake of doing a show last quarter, right before finals, which was not it,” Hill said, laughing. “The queen who hosted it was like ‘we need to get you drunk, before you need to go write those papers.’”

Aceves and Hill didn’t start out booking shows and coordinating acts. Instead, they started experimenting with makeup at home and then started performing at drag shows, open to all levels of experience.

Aceves was worried about how they’d do in a competition. For much of their drag history, performances at home in front of their mirror were as far as they went.

“I started doing drag in the privacy of my own one-bedroom apartment at the beginning of the pandemic when things first shut down,” Aceves said. “I did it as a way of expressing my gender and trying to find some peace of mind.”

Through this at-home style of drag, Aceves found ways to sharpen their skills.

“I’ve grown up with drag, and I’ve admired so many of the Chicago drag performers,” Aceves said. “I would watch tutorials on YouTube, and I would follow [other performers] and kind of see what they were doing and try and mimic that.”

Drag has always been a means of defying societal gender norms. Gay venues were a way for the LGBTQ community to gather and express this defiance without fear of retaliation.

“By putting on drag, we are saying gender isn’t real,” Aceves said. “We challenge the idea that there’s a certain way to be a woman. There’s a certain way to be a man. There’s no way to be anything.”

The predominantly white Chicago drag scene is due for a change, and Victoria thinks Boystown venues and bookers have an obligation to make change. This change starts with diversifying their bills (the list of performers for the evening).

“I encourage them to reflect on how they build their bills,” Victoria said. “I would really like to see the clubs giving opportunities to people of color, particularly black, trans performers.”

As awareness of the overwhelmingly white makeup of drag bookings in Boystown comes to the foreground, Victoria is optimistic about the future of the Chicago drag scene.

“We’re on the verge of a Chicago drag renaissance,” Victoria said. “I feel pretty optimistic.”