COMMENTARY: Fair Play Act won’t let the NCAA hide behind old excuses

AP Photo/David J. Phillip, File

NCAA President Mark Emmert speaks during a March 29, 2018 news conference at the Final Four NCAA college basketball tournament, in San Antonio. The NCAA is on its heels again, playing defense of its archaic amateurism rules after missing an opportunity to get out in front of an issue.

A storm is brewing in college athletics – one that the NCAA can’t contain anymore. It’s time to pay their student-athletes.

For 113 years, the NCAA has prevented its student-athletes from getting paid or making money based off their likeness, as well as barring them from accepting any endorsement deals. Throughout those 113 years, there has been a lot of talk about student-athletes getting paid. There have even been lawsuits that went to court to figure out this issue — and in all of these cases, the NCAA won.

Every time it might seem like the NCAA would have to give in and allow student-athletes to make money while in college, either the courts would rule in their favor or they would fall back on their same, lame argument: amateurism.

The NCAA’s main point this whole time has been that people who go to college and play sports are students first and athletes second, meaning that since they aren’t considered “professional athletes,” they can’t make any money while they are in college.

For the majority of its existence as a “non-profit organization,” that argument has favored the NCAA, until a recent bill signed by California Governor Gavin Newsom last week that would allow college athletes to negotiate their own contracts with third parties over the commercial use of their names, images and likenesses.

The Fair Pay to Play Act would not convert college athletes to employees or allow them to unionize. The act also prevents athletes from agreeing to an endorsement deal with a company that already has a deal with the school they are attending. This is the first time that a state has passed a bill that would allow college athletes to profit off their own personal brand.

The NCAA came out with a response immediately following this decision, and arguing that this bill is “unconstitutional” and gives California schools an “unfair recruiting advantage.”

For an organization that in just 2016 had revenue exceeding $1 billion, net assets exceeding $400 million and a payroll of more than $70 million — $2.4 million of which went to its president, Mark Emmert that – is an incredibly weak argument.

For the NCAA to come out and argue that this bill, which would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2023, would create an “unfair recruiting advantage,” is utterly ridiculous. In college football, even without this bill, not every school has the same recruiting advantages that some of the powerhouse colleges do. For example, having Hall-of-Fame coach like Nick Saban and an uninterrupted string of championship banners is also, quite simply, an unfair recruiting advantage for Alabama.

In both college football and basketball, there are a handful of programs from each sport that dominate recruiting year in, year out, and that ends up showing at the end of each season. For the NCAA, which said they care about keeping the playing field level for everyone, that really doesn’t matter because their ultimate goal is to make money.

Having teams like Alabama and Ohio State in college football and the likes of Duke and North Carolina in college basketball constantly get the best players, no matter what recruiting violations they might be committing, suits the NCAA.

So for the NCAA, this statement is just to cover themselves from the onslaught of pressure it is starting to receive from the public. With professional athletes like NBA superstar LeBron James coming out and endorsing this bill, the NCAA had no choice but to make this ludicrous statement.

The NCAA has also argued in the past that college athletes are students first, and doesn’t consider them to be professional athletes. That argument might be even worse than the previous one about recruiting advantages.

For starters, the NCAA can just look at one of its most premier college basketball programs, North Carolina, and that becomes a moot point.

In 2014, a massive scandal hit the NCAA and North Carolina which detailed an 18-year-long effort by the school to keep their athletes eligible by having them take “paper classes.” In the report, football coaches, as well as advisers in the school, were telling athletes to take specific classes that would boost their GPA.

Even with all of that crippling evidence that showed North Carolina bending over backwards to keep their athletes eligible, the NCAA did not sanction the university.

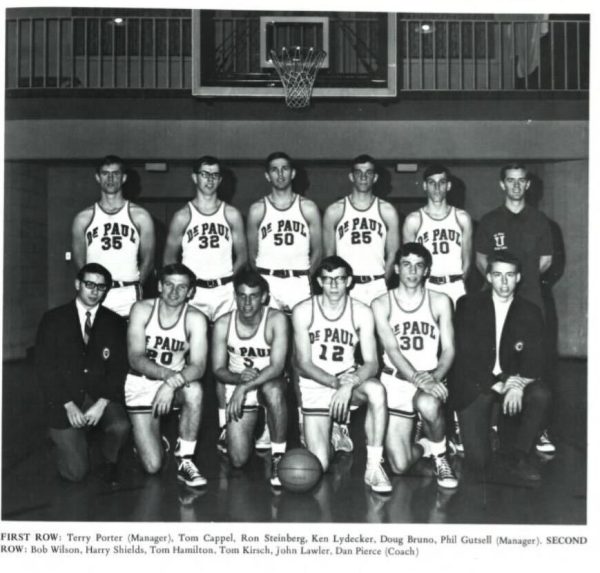

Robert Kallen, a DePaul clinical professor of economics and director of the masters program in economics and policy analysis and expert on the NCAA, believes that for major change to occur in the NCAA regarding these types of issues, university presidents need to step up and force change to happen within their own schools.

“University presidents are not naiive; they know what’s going on,” Kallen said. “They are either setting up zones of plausible deniability or just turning the other way. When all is set and done, it’s going to take some very strong university presidents to finally say, instead of building buildings and looking at the endowment, maybe I should look at what we are doing, which includes student debt and the exploitation of athletic students. If you want change to occur, it needs to come from the university presidents or from the board of trustees.”

While the NCAA keeps saying it cares about athletes receiving an education, their decision on important matters like the North Carolina case smells of the organization trying to protect a massive brand rather than backing up its words on the importance of receiving an education.

With the California bill sparking major uproar from the NCAA, it has also provoked athletic directors around the country to make their voices heard, including DePaul Athletic Director Jean Lenti Ponsetto.

At the Chicago Sports Summit on Wednesday, Lenti Ponsetto expressed her concerns about paying college athletes.

“[Having to negotiate salaries with athletes] would be the demise of intercollegiate athletics as we know it,” she said.

For Lenti Ponsetto to make that comment is another example of someone who holds major power in college athletics who does not understand the bill at face value. When The DePaulia requested a comment from her regarding California’s bill, she supported players using their name, image and likeness to enhance their collegiate experience.

By DePaul’s own actions regarding amateurism and eligibility shows the university doesn’t have much ground to stand on. This past summer, the NCAA ruled that the men’s basketball program participated in illegal recruiting activities when a former associate head coach arranged for the assistant director of basketball operations to travel out of the state to live with a recruit to ensure that he completed NCAA core courses and became immediately eligible to compete, according to a news release.

Situations like this, and much worse, have come up in schools like North Carolina, where athletic departments are treating their players as athletes first and students second. Because, for a lot of these programs, keeping their students eligible to play is more important than helping them complete their four-year degrees. In other words, academic integrity doesn’t seem to be a priority to begin with.

Emmert and the NCAA-labeled name, image and likeness rights an “existential threat” to the collegiate model. This so-called collegiate model should exude a level of amateurism and lack of distinctness between universities. Blue bloods like Ohio State, Michigan, Notre Dame, Texas, Duke, Alabama and Oregon, to name a few, shouldn’t be these gigantic conglomerates of gross income and flashy lives. Coaches and athletic directors are purchasing million-dollar homes off salaries that rely off of the success of their unpaid workers. And alumni can’t even buy dinner for one of their school’s star athletes.

The existential threat talk is nonsense in this regard. The amateurism debate is a way for the people in charge to have full control over the players who help them keep their million-dollar contracts.

Dave • Oct 7, 2019 at 4:18 pm

There are two reasons the NCAA and schools have pushed back on this. One, they are afraid of corruption. What will probably happen is a few boosters and/or companies will throw a lot of money at the star QB or the star point guard for really doing nothing, especially without any guidelines set forth to follow. If other schools cannot compete with this, it’s a problem. If those schools get kicked out of the NCAA and TV money and tournament money dries up, it’s going to have a negative effect on the schools in States where players are getting paid. But the real reason is as follows. These colleges have spent BILLIONS developing their school and athletic program and billions a year to maintain it. That money needs to be paid back somehow, and it’s paid back from revenue mostly from football and basketball which usually generate the most money. If a player’s likeness only has value because of that school investment, then the school is going to want to control that. That revenue helps the school and athletic program exist. Those players are more reliant on the system succeeding than any other athlete at the school ,because most other athletes are paying part or all of their tuition. Furthermore, this notion that college programs are dripping with money is simply not true. About 75% of D1 football teams lose money. Uconn had to basically throw away 20,000 unsold bowl tickets a few years ago because no one wanted to buy them. Cal is currently paying 18 million a year in debt payments on their stadium which goes up to 26 million in several years and continues many many years into the future. Their athletic department is currently 22 million a year in the red because of those loan payments. So which athletes do we want to pay exactly because the majority of them don not generate net revenue? Of course a school doesn’t want an athlete making money on their dime when they are losing 22 million dollars a year giving that athlete an opportunity to attend school for free and market himself or herself to professional teams. I am not sure why this is difficult for some people to understand. Lastly, the majority of tournament and bowl revenue goes directly back to colleges and helps them fund the very athletic programs people are complaining about.