Lincoln Park restaurants, retail suffer in the Covid economy

Restaurants along 2000 N Halsted in Chicago’s Lincoln Park neighborhood.

The Lincoln Park neighborhood’s atmosphere was empty after March 2020 when DePaul emptied its campus and sent students home to limit the spread of Covid-19. As students went away, local restaurants suffered.

“When it comes to managing my money, I’ve always been pretty good at it,” said DePaul senior Cole Lopardo. “I keep close tabs on my finances and pretty much memorize how much money I have and where that money is going. I try to limit how much I go out or try new things because of Covid.”

The insidious virus that has claimed more than 22,000 lives in Illinois and nearly 500,000 nationwide has had a direct, if uneven, impact on the businesses that surround DePaul’s Lincoln Park campus. Business owners and city officials say dining, entertainment, retail and tourism have suffered the most while some enterprises, including delivery services, have thrived and even grown during the pandemic.

According to Robin Hammond, vice president of the Lincoln Park Chamber of Commerce, the effects of the pandemic on Lincoln Park’s economy has been similar to its national impact.

Restaurants, bars and retail outlets continue to struggle and nationwide and total closures have started to increase. At the same time, according to data compiled by Yelp, businesses providing home, local and professional services have been able to withstand the effects of the pandemic particularly well.

“There are businesses that actually have fared well, because they have services that are needed during this time,” Hammond said. “The home sector, real estate agents, construction companies, renovation companies have actually done really well during this time because more people have been working from home.”

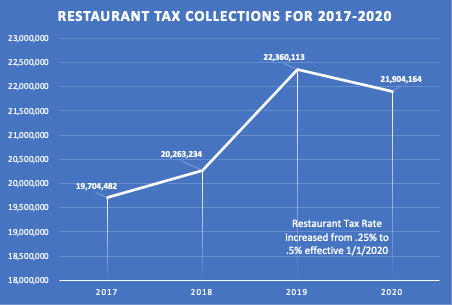

Restaurant tax collections decreased by 2 percent from 2019 despite the increased tax rate due to decreased restaurant revenue and profits, according to data obtained through FOIA from Chicago’s Department of Finance (DOF) Tax Division.

The city does not break down tax revenue by neighborhood, so it is difficult to know how Lincoln Park fared compared to other areas of Chicago.

Kristen Cabanban, director of public affairs of the city’s Office of Budget and Management at the Department of Finance, said the restaurant tax rate increased from 0.25 percent to 0.5 percent in January 2020, just weeks before the pandemic hit.

Under normal circumstances, the city should have seen an almost doubling of collections from prior years, Cabanban explained.

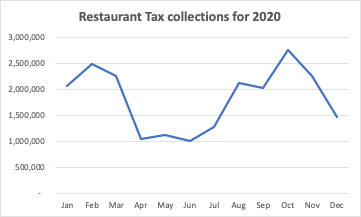

“The restaurant industry was hit extremely hard as a result of the pandemic,” Cabanban said. “To provide some financial relief to local businesses, the Lightfoot administration delayed tax remittals during peak Covid last year.”

Restaurants experienced lower revenue during Chicago’s profitable months during the summer due to the pandemic.

Despite large amounts of revenue lost due to the economic downturn caused by Covid-19, Cook County’s preliminary 2020 budget results for the fiscal year ending Nov. 30 shows a positive year-end balance.

Based on the monthly report provided by the Cook County Bureau of Finance to the Cook County Board of Commissioners, the County expects to end the year with a positive balance of $154.7 million in the General Fund and $259.2 million in the Health Fund on a budgetary basis, according to the Civic Federation.

Craig Richardson, co-owner of Batter and Berries on Lincoln Avenue, has been running his breakfast, brunch and lunch restaurant since the establishment first opened its doors to the Lincoln Park community in 2012.

For Richardson, 2020 ended up being one of the establishment’s most challenging years since the restaurant’s first year in business.

Due to the closure and restrictions of dining rooms throughout the year, Richardson said it’s been challenging to maintain a full staff while also generating revenue. He had to cut about a third of his total staff to keep expenses low.

“We had to trim our staff down because there wasn’t enough business and certain positions just weren’t necessary,” Richardson said. “We had to basically run on a skeleton crew to try to keep expenses low.”

Batter and Berries continued to operate every day with a smaller staff and fewer hours throughout the city’s reopening phase.

“Around mid-summer we only opened up the dining room for five days a week instead of seven, and the other two days, we still did delivery and carryout where we just didn’t do any sit-down service,” Richardson said.

As the city’s reopening plan progressed, Batter and Berries was able to increase its indoor capacity to 40 percent, seven days a week. However, that didn’t last long as the rising Covid-19 case numbers in November led Mayor Lightfoot to, once again, order restaurants to shut down indoor dining.

Richardson said that although his establishment was operating with fewer clients and had less money coming in, his business expenses remained the same.

“Your expenses don’t go down,” Richardson said. “The rent is still the same, there’s still a certain amount of electricity and gas that we use. A lot of your expenses don’t decrease proportionately to your income.”

Richardson’s costs, such as insurance and equipment, remained fixed. The thought of possibly being the next restaurant to close its doors to the Lincoln Park community is one that establishment owners like Richarsdon commonly faced as the city rules fluctuated depending on coronavirus case numbers.

“The earlier part of the pandemic was rougher, emotionally,” Richardson said. “In terms of not being able to give employees hours, not knowing how they’re going to survive, not knowing if your business is going to survive, seeing other businesses fold up, some friends having to close their business, wondering if you’re next.”

Last year, on Dec. 14, Devil Dawgs, Lincoln Park’s favorite stop for classic milkshakes, burgers and iconic Chicago style hot dogs, closed down its flagship location after 10 years as Covid-19 reduced customers and its lease ended.

“When I heard the news, I was a bit stunned at first, given how long the establishment has been around the Lincoln Park area, but at the same time I was not too surprised,” DePaul senior Thomas Billups said. “The reason being is because given how much Covid-19 has impacted the business industry and caused campuses across the nation to close down and convert online, I knew the lack of students as customers was going to impact Devil Dawgs business and unfortunately, it did.”

There was a collective feeling of sadness when the news broke about the beloved hot dog location.

“[Devil Dawgs] was basically the only somewhat late-night food near campus,” said junior Lauren Lewis. “What are people going to eat now?”

“Devil Dawgs made my street feel safe because there were always so many people around,” said junior Angelina Moore. “But it makes me sad that it’s gone and that I don’t have a yummy place to eat right outside anymore.”

Nationwide, the Yelp data shows how the pandemic has left economic destruction in its wake, particularly last summer. Between the beginning of the pandemic in March and the end of August, nearly 164,000 businesses in the U.S. were forced to close. Since then, in a glimmer of better news, the rate of business closures has begun to drop.

“There have been businesses that have closed, but I’m heartened by the percentage of businesses that are continuing to survive and continuing to find ways to stay in business, being able to work with their landlords and continue to serve their customers,” Hammond said.

Meanwhile, for Chad Bertelsman, the general manager of Chez Moi, the grand opening of his new restaurant French Quiche located at 2210 N Halsted St. on Nov.r 13, 2020 was a successful launch and addition to the Lincoln Park community.

“We started working on [French Quiche] in 2019 and we had way too much time and money invested just to walk away from it,” Bertelsman said. “We could have continued paying rent and not make any money or we can open up and at least break even so we can add some jobs to the economy.”

Although Chez Moi, the French cuisine restaurant located on 2100 N Halsted St., had to lower its staff during the beginning of the pandemic, its business was bustling by summer and fall due to the city’s bearable weather.

The high temperatures and clear weather allowed Chez Moi to operate with outdoor dining once indoor dining was no longer permitted.

“Our September 2020 is looking at higher sales and higher profits in September 2020 to 2019, that’s due just to the fact that we had absolutely beautiful weather almost every day,” Bertelsman said.

Even with 45 degree weather, Chez Moi was still providing outdoor service to its clients. Bertelsman said that not only did the weather help the business of Chez Moi but their supported clients also played a significant role.

“We were also very lucky that so many of our great regulars are so kind and generous and the tips that they leave are phenomenal anywhere from 30 percent to 40 percent to more than 100 percent,” Bertelsman said. “We have a really great regular who consistently leaves more than 100 percent tip just because he knows [our servers] have had a tough time these last 10 months.”

From financially supporting the restaurant to simply having clients stop by to greet Chez Moi workers, residents and foodies were able to bring a sense of hope during a year of uncertainty to Lincoln Park’s restaurant business.

“The people in the neighborhood feel a lot more part of our properties because we’re there, we remember them and we talked to them,” Bertelsman said. “They really come out to support us. We have a regular elder who doesn’t want to go out yet but he keeps sending us a check for $200 that he’s been doing every month since last March to make sure the restaurants got resources we need. Those sorts of things are very touching and Lincoln Park has really embraced us.”