OPINION: It’s time to run-off the runoff, Ranked-choice voting for Chicago

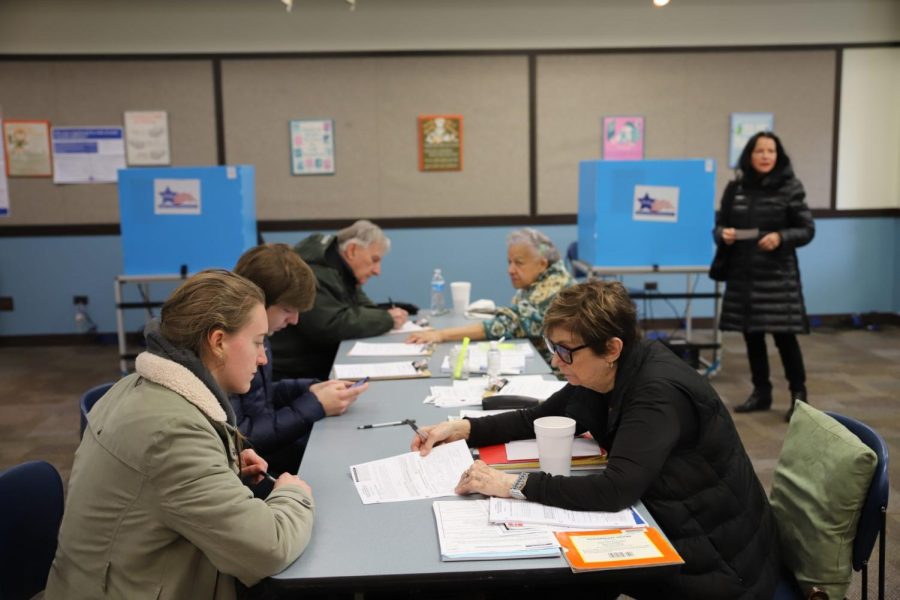

Chicagoan’s at the Lincoln Park Public Library cast their votes for the consolidated municipal election Friday Feb. 24. The polling site will reopen for the runoff election on April 4.

Much is left undecided after Tuesday’s municipal election, the fate of the mayoral office and many of the aldermanic seats now hang in the balance of a runoff election scheduled for April 4. A runoff occurs when candidates are unable to secure 50% or more of the vote in an election. The first time a runoff was needed was in the 2015 municipal election, between Rahm Emanuel and Jesus “Chuy” Garcia. This inevitably drags the election season on for an additional six weeks and costs taxpayers millions to operate a runoff.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. A better option exists. Ranked-choice voting (RCV), also known as instant runoff voting, stands as a way to avoid runoff and allow voters to choose what they truly want rather than strategically. In many cases, voters feel compelled to vote for the most “viable” candidate rather than who they truly want to win out of fear of splitting the vote.

In ranked-choice voting, instead of choosing just one candidate, voters rank the candidates they align with most in order of preference. To win an election in Illinois, candidates need to win more than 50% of the votes. The candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated. If you voted for that candidate, your vote goes to your second choice automatically. The process repeats until a candidate wins a majority.

In the 2019 municipal runoffs, more than 30,000 less voters casted their ballots than in the general election. Municipal election turnout is already historically low, according to the Chicago Board of Elections (CBEC). There is no reason to put another barrier in the way of people’s ability to choose their elected officials.

However, CBEC alone doesn’t have the power to alter the way elections are currently conducted.

“This would be something that would have to be created legislatively,” said Max Bever, director of Public Information for the Chicago Board of Elections. “It wouldn’t be a decision … by the board.”

The change could save taxpayers in Chicago up to $30 million during municipal election years, according to CBEC. For this year’s municipal elections, the city allocated $60 million. Those funds broke down to $30 million for the general election and $30 million for the runoff.

If Chicago made the move to a ranked-choice voting system, CBEC wants the change to be intentional, not simply a measure to save the city money.

“Hopefully, this isn’t just a cost-cutting measure,” Bever said. “This isn’t just an idea to be like we can get rid of runoff elections, and we can just cut that $30 million, there will be a lot of work that would need to be done to fully educate Chicago’s voters about this change.”

This change would require a massive campaign to educate voters, especially elderly and non-English speaking voters.

Evanston recently adopted the use of ranked-choice voting for its municipal elections beginning in 2025.

“I think [Evanston Board of Elections] got some time, they’re trying to communicate to voters,” Bever said. “So I think there’s a lot of lessons and a lot of info out there that would be good for the city to learn about this decision.”

Cassandra Rice, a resident of Logan square believes ranked-choice voting would be a move in the right direction for a more representative democracy.

“With ranked-choice voting, you’re able to rank [candidates] with different platforms,” Rice said. “So then, as those results get tabulated, it really is an accurate representation of preferences for different candidates, because you’re able to really pick who, you know, if it’s not this person… then I’d be fine with the next one.”

The runoff system relies on voters to stay engaged throughout the additional six weeks of election season and cast their vote again. This is an unnecessary burden, especially considering the disengagement in municipal elections.

“Having to get out on Election Day is still very very prohibitive for a lot of people,” Rice said. “When you have a system like we do in Chicago, where there’s this runoff process, I think it’s an attempt to try and be more equitable or fair to the candidates in a way, but it’s also kind of just a messier process of what rank choice voting would do in one fell swoop.”

While a lot of work must be done to educate voters to not alienate or create worse disparities in access to the polls, ranked-choice voting is an essential part of creating a more equitable election system in Chicago. Allowing people to vote for people they believe in instead of who they believe is most likely to win, makes elections as seamless and cost-effective as possible.