Freedom of the press comes at a cost. But who’s going to foot the bill?

A newsstand near Tribune Tower on Michigan Avenue.

Freedom of the press is a quintessential part of our democracy.

In 1892, journalist and civil rights leader Ida B. Wells investigated and reported on lynchings in the South, making data on racial discrimination and lynching accessible to the public for the first time in the U.S., which led to the publishing of her 1895 piece called, “The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States.”

Fast forward 100 years: Bob Woodward and Carl Berstein of the Washington Post uncovered former President Richard Nixon’s attempted cover-up of the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters. The investigation led to Nixon’s resignation and the expansion of Congressional power.

And in 2016, Marisa Kwiatkowski, Mark Alesia and Tim Evans of the IndyStar investigated USA Gymnastics’ failure to report sexual assault cases, which led to the conviction of serial rapist and sex offender Larry Nassar who has been sentenced to life in prison.

But from laying off entire photo staffs to hedge fund buyouts to political leaders inciting distrust in reporters at large, the news industry has never been more vulnerable, especially in the wake of Covid-19.

According to Jacob Nelson, assistant professor at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, news organizations are mere shells of what they once were, which underscores the economic strain and oftentimes lack of quality in the news we see today.

“Because news organizations are so strapped for cash, they’ve had to cut back in really serious ways,” Nelson said. “So, we’re seeing a lot less coverage than we ever did before. And we’re seeing difficult decisions being made, such as which beats do newsrooms get rid of? Which stories can we afford to not tell? And that means communities are not getting the coverage that they deserve.”

The economic strain on newsrooms comes from the evolution of the news business. But the rate that the business is evolving is too fast for publishers to keep up.

Tim Franklin, senior associate dean of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, said the news business model is “completely broken” because digital ad revenue once allotted to news publishers has shifted over to monoliths such as Google and Facebook. This has cost newsrooms their financial stability as well as their readership since the dawn of the digital age.

According to a 2020 Pew Research Center data analysis, newspaper advertising revenue fell from $37.8 billion in 2008 to $14.3 billion in 2018, and the circulation of U.S. daily newspapers — the number of copies distributed on an average day — both digital and print has declined by 8 percent.

As publications lose money from the redistribution of digital ad revenue, readers and newsrooms disappear with it.

According to a University of North Carolina study on the increasing number of news deserts — an uncovered geographical area that has few or no news outlets and receives little coverage — nearly one in five U.S. newspapers have closed, leaving hundreds of journalists unemployed and dozens of communities forgotten.

Some argue the news industry is dying, but it can be saved if with appropriate, effective action.

In order to ensure the news industry’s survival, Franklin said it’s up to publishers to reshape their news business model in favor of monetizing the news; this way, newsrooms can refocus news gathering back on community trust-building and engagement.

“I think the key for all news organizations these days is transparency,” Franklin said. “To be open and honest with the public about the news reporting, about errors that are committed, about, in some cases, the process of how stories were gathered in a way gives the public trust. But if you’re not transparent and you’re not engaged with your community or your audience, that’s where trust really erodes.”

Franklin said the news business model is “completely shattered,” and it’s time newsrooms reinvent their approach to ensure they stay afloat.

Here are some of the ways newsrooms can help protect our freedom of the press.

According to Josh Stearns, the program director of Democracy Fund — an independent foundation which aims to improve the democratic process in the U.S. — there are three easy steps the average news consumer can take to play a role in protecting their right to information.

By easing the news industry’s financial strain through support from the average citizen to the billionaires, it can help newsrooms focus on other key issues. From improving the quality of the content produced to interacting with communities to dismantling systemic racism and patriarchal structures in the industry, monetary aid can help newsrooms get back to the original mission of the job — to find, report and defend the truth with excellence and integrity.

According to Chicago Sun-Times high school sports editor Michael O’Brien, he used to have what he called an “army” of reporters covering the high school sports beat. He estimated 46 full-timers, 60 freelancers and 30 photographers.

But in 2014, when the Sun-Times suburban newspapers were sold to the Chicago Tribune, O’Brien said one day he came into the office and his colleagues were packing up and saying goodbye. Now, O’Brien is the only full-time high school sports reporter for the publication.

Because so many of his coworkers left or faced layoffs, it forced O’Brien to focus on readership. And he said the numbers were “striking.”

“90 percent of our traffic was boys’ basketball and football,” O’Brien said. “And it was an incredible amount of money that we were spending on things like track and soccer and all the other stuff, and even baseball didn’t have any kind of an audience. So it just became really clear — when you’re looking at those numbers [and] what was left — what we would do.”

Now, hundreds of young women and men in the Chicago area are being excluded and denied equal news coverage in their own hometown because football and high school boys’ basketball is more in-demand, and the newsroom saves money by not having as many reporters covering the breadth of high school sports.

“For me, I think the most disappointing part of it was the numbers kind of held up in the readers’ response,” O’Brien said. “There was no outcry.”

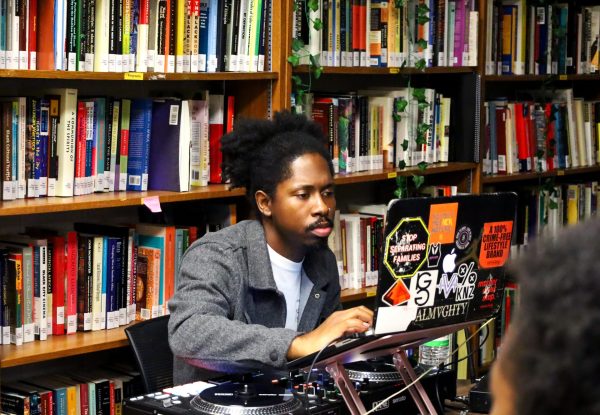

Smaller newsrooms that are more up-and-coming and free of decades of institutional baggage such as Block Club Chicago and City Bureau have the money and the people to make strides to ensure more communities — especially those that are underrepresented and disenfranchised — are covered by journalists with consistent attention.

Even though Block Club Chicago’s headquarters is located in the Loop, reporters are placed by the publication to cover specific Chicago neighborhoods, which allows communities to have a relationship with reporters.

City Bureau’s director of growth strategy Andrew Herrera said journalists’ priorities need to lie in transparency and building community trust through their reporting.

“People are beginning to feel the absence of good media,” Herrera said. “The hope and the optimism is that we can push back against this kind of oppressive, monolithic, corporate-driven media culture where there’s only a set number of approved perspectives, and we can find our voice again [sic] around shared interests and around shared beliefs.”

When it comes to saving the industry, journalists are the first line of defense.

Last summer, a special team of editors from the Wall Street Journal completed an audit of what the publication is doing right and getting wrong. They called it “The Content Review.”

Addressing issues such as news gathering strategies to institutional racism in journalism, Wall Street Journal’s special team created a blueprint for how the paper should remake itself to ensure its future, but most people in the newsroom haven’t yet seen the report and its content hasn’t been completely addressed by higher-ups.

Journalists are listening to the public — and themselves — and trying to make meaningful change. But running things up the flagpole in a system in shambles makes it harder for newsrooms to evolve quickly.

According to Wall Street Journal assistant managing editor for talent Sarah Rabil, the future of quality, fair and accessible news coverage is in the hands of budding reporters.

“I get to spend a lot of time with student journalists, a lot of time with interns, and it makes me increasingly optimistic about the future of journalism,” Rabil said. “I think the fact that this generation also cares about the policies of newsrooms, the practices, their peers and that relationship, that also gives me a lot of hope.”

Ensuring the survival of the news industry starts with the publishers. But it depends on everyone. Between publishers bargaining with Google and Facebook and consumers donating to their local news outlet, everyone can play a role in creating and demanding access to quality news now and for the future.

It’s an unalienable right, after all.