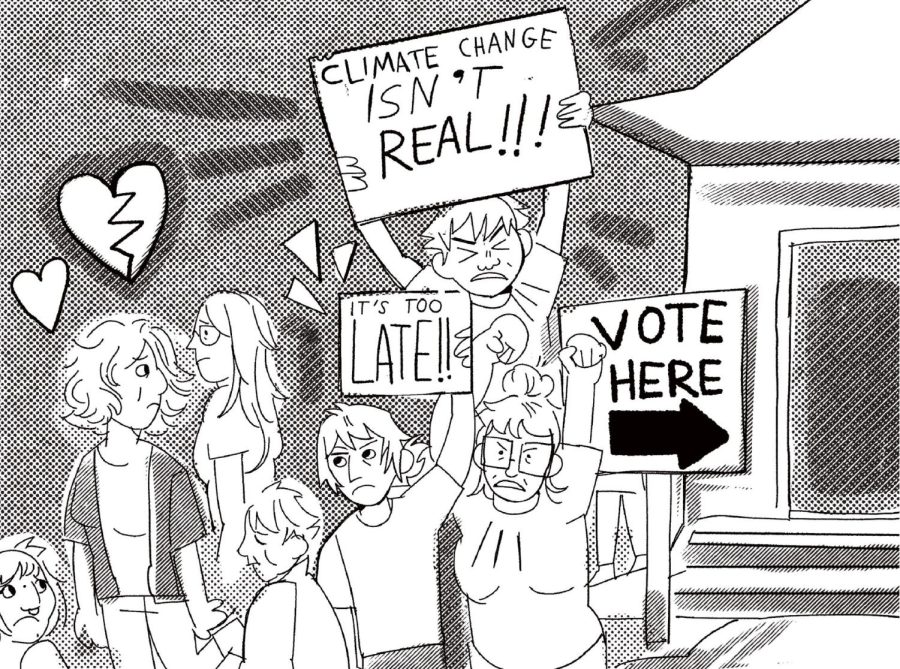

Climate doomist philosophy will fulfill its own destiny

Climate patterns are shifting, causing extreme weather, death and destruction. Individuals account for a small fraction of global emissions, and oil and gas companies lobby politicians to write legislation in their favor. Seeing the toll of climate change can make mitigating or reversing its impacts feel hopeless as an individual.

Climate doomism is the idea that global warming will eventually lead to the death of all life on Earth and that there is nothing that can be done to stop climate change or that governments will never take the steps necessary to stop climate change.

“With our current economic and political system, any sort of positive change can feel impossible,” said DePaul junior and environmental science major William Szromba. “What difference does it make that you drive a fuel efficient Prius if celebrities are taking hundreds of private flights a year? I think feeling hopeless and apathetic in a situation like this is understandable, but I think that the apathy and nihilism that climate doomism generates is ultimately counterproductive.”

I have noticed that some people justify wasteful tendencies by stating their individual footprint is nothing compared to major corporations’ impacts. Since 1988, 100 companies have produced 71% of emissions. While most people can never come close to producing as many emissions as a company, that does not mean that people should not be opting for paper over plastic, foregoing the straw or taking public transport.

“I think that individuals can certainly act in ways that help them feel better about their conscience, they can help them feel better about not contributing to the problem,” said Barbara Willard, DePaul communication studies associate professor. “Will that make a significant change? No, but what individuals can do is become engaged and involved.”

There are many ways to get involved, such as protesting, reaching out to politicians, making sustainable personal choices and planting native trees and gardens in local communities.

“I have a student who worked on creating habitat for the rusty patch [species of] bumblebee by planting host plants in backyards and parks and things like that,” said DePaul environmental science associate professor Christie Klimas. “That’s highly actionable. There’s projects like that about monarch butterflies … I think we sometimes don’t focus on this because we need system level change as well.”

Small changes can help biodiversity, but it is also important to champion for larger reform by urging governments to pass legislation that will curb the fossil fuel industry, create sustainable energy alternatives and promote land conservation.

“Stop settling for the lesser of two evils when it comes to elections in this country,” Szromba said. “Campaigning for more direct action and protests against fossil fuel companies is more productive … I think civil disobedience is a very effective tool when it comes to preventing further environmental destruction.”

While the Earth’s situation is dire and its average surface temperature has already warmed 2 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880, with the 10 hottest years on record occurring since 2010, there is still hope to slow global warming and reduce its impacts during our life. Reversing the impacts, however, might still take more time than people have in this lifetime.

“It really depends on how much we can stop the fossil fuel industry from continuing to tap into the fossil fuel reserves that we have and using those fossil fuels,” Willard said. “And if we can do that, then that does not mean that we still won’t lose species or that the Earth won’t continue to warm, but it will mean that we will lose less, and there will be less damage, there will be less catastrophe.”

There are many ways in which we can exercise our voices to champion clean energy and a sustainable future. One way is championing the Indigenous Land Back movement, which fights to give Indigenous people control over the resources on their land.

“There have been a couple of studies in the Amazon that look at, in essence, who’s most effective in conservation,” Klimas said. “And indigenous groups, by and large, are significantly better at maintaining and conserving biodiversity and … an intact Amazonian forest than all other groups.”

Indigenous people all over the world have a long history of living sustainably and in harmony with the land and with nature. They have some of the smallest carbon footprints in the world and are far more effective in conserving land than non-Indigenous people.

There is so much dismissal and apathy surrounding climate change, and a large part of that is due to the rhetoric that there is little that humans can do to combat climate change.

Recently, scientists discovered a kind of mushroom that is able to digest plastic.

“Consistently, we’re finding ways to combat our environmental problems,” Willard said. “Scientists are hard at work coming up with new innovations, so why can’t we also teach that as well and stress those positive scientific outcomes?”

Focusing on the positives of climate news might help people understand what they can do to combat climate change and encourage more people to be proactive about climate change.

Klimas recalled a Brazilian saying she knew of.

“There’s this big Amazonian forest fire and there’s a hummingbird, and the hummingbird is carrying water in its beak and dropping it on the forest fire,” Klimas said. “And another animal comes up to it and says, ‘This isn’t going to make a difference,’ and the hummingbird says, ‘I’m just doing my part and waiting for everybody else.’”