DePaul political science professors speak on Capitol riots

Supporters of President Donald Trump climb the west wall of the the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday, Jan. 6, 2021, in Washington. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)

It has been almost three weeks since the insurrection at the nation’s Capitol building.

That Wednesday, thousands of protestors in attendance of former President Trump’s rally in Washington D.C. descended on members of Congress. Inspired by a conspiracy theory of ballot counting fraud, supporters of Trump ran down Capitol police. They picked up metal barricades and knocked down officers in order to gain entrance. Pipe bombs were found in both the Republican and Democratic National Committee headquarter buildings. Soon after they gained entry into the senate floor – broken glass trailing their path – confederate flags started to flank the balconies of the Capitol steps.

Last Wednesday, DePaul’s political science department held a community panel to dissect the insurrection.

“We have a population of people who would shatter our nation rather than share it – and for whom democracy is simply not a consideration,” said panelist and political science professor Valerie Johnson.

Johnson believes this population is responsible for the events that took place at the Capitol.

“When I look at the insurrection … I asked myself, ‘How could any democracy-loving American actually justify an attempt to steal an election? It was never about democracy – it was winning, and it was about a quest for power,” Johnson said.

Though this day felt new to most of America, the heart of the issue is nothing new.

During the Trump administration, the United States’ divisiveness intensified, and some believe the two-party system operating in the nation is the problem.

Erik Tillman, a panelist and political science professor, said that the U.S.’ political system is unique – but that’s not always good in the long run.

“It creates an unhealthy environment that reinforces the intensity polarization and the willingness of elected leaders to be tempted to break democratic and constitutional norms.”

For the political left, the dedication is a return to democracy, and on the political right, there’s been an aversion to democracy in favor of authoritarianism, Tillman said.

“What activates authoritarians is whenever they perceive threats to the oneness and sameness in society,” Tillman said.

Tillman said that the current threats to this “oneness” are the promotion of different races, multicultural and sexual preferences that are seen in society today.

“Then, behaviors and attitudes that are authoritarian in nature become ‘justified’ even if they’re quite radical – like the events of January 6th,” Tillman said.

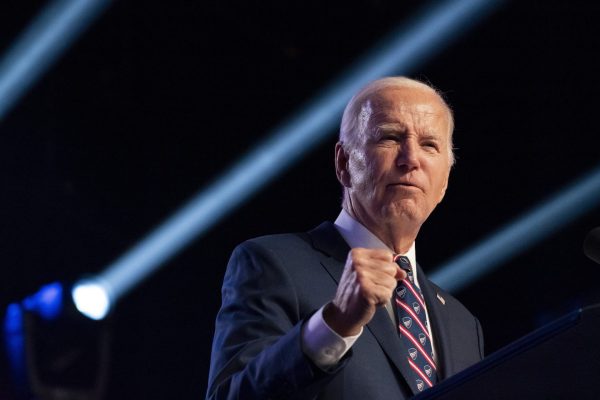

After the events of the Capitol breach, many were worried a similar event would unfold the day Joe Biden was sworn into presidency. Evidence of violent plans of attack began to emerge, forcing security in the nation’s capital to be on heightened alert for Inauguration Day.

In the vetting process of this security, the Pentagon found and dismissed a dozen National Guard members found to be in connection with right-wing extremism.

That morning, the city of Washington D.C. was barricaded. Though crowds were meant to be small to enforce social distancing guidelines, efforts to increase security were also at play. Companies like AirBNB and airlines had refunded anyone with reservations leading up to the day. This meant that the normal crowd that usually consisted of hundreds of thousands was reduced to roughly 2,000 attendees.

Large, green and gray shields flanked the new administrations left and right, preventing any potential sniper attacks. 25,000 troops were at their post for the proceedings, proving to the nation that these threats from weeks prior were being taken seriously by the government.

Aside from a few scattered protests, the day was able to go on without any breach in security, allowing those around the country to zero in on Biden’s inaugural speech.

It was a message centralized on the idea of unity.

“Uniting to fight the foes we face: anger, resentment, hatred, extremism, lawlessness, violence, disease, joblessness and hopelessness. With unity, we can do great things, important things. We can right wrongs,” said President Biden in his address to the American people.

However, some are not quick to believe this administration will be enough to bridge the gap.

“I don’t know that Joe Biden necessarily has the stomach to approach these issues the same way that Bernie Sanders might have or Elizabeth Warren,” said David Williams, a panelist and political theory professor.

While Williams believes the absence of Trump’s instigations will help, he acknowledged that a new president won’t solve everything.

“If we want to get back down to a baseline that is healthier, it’s going to require a more systematic approach to addressing those circumstances that have fueled those tensions in the first place,” Williams said.

Many were satisfied with Biden’s speech and future plans, but acknowledge that words aren’t enough.

“My sense is that Biden said the right things… I think actions that follow are really really critical,” said panelist and political science professor Wayne Steger.

However, Steger believes that if the pandemic and economy are not dealt with first, there’s no hope of resolving any other issues. He suggested failing to do so would make the divide even worse.

Going forward, the inability to solve the partisan issues of the nation will come at the sacrifice of its democracy.

“For me, the most immediate lesson on Inauguration Day from the Trump administration is just how fragile democracy is… we are as vulnerable as any other democracy and we need to be on guard against any further crumbling of it, because we’re not that far from the edge,” Williams said.